Mark Scheme

Introduction

The information provided for each question is intended to be a guide to the kind of answers anticipated and is neither exhaustive nor prescriptive. All appropriate responses should be given credit.

Level of response marking instructions

Level of response mark schemes are broken down into four levels (where appropriate). Read through the student's answer and annotate it (as instructed) to show the qualities that are being looked for. You can then award a mark.

You should refer to the standardising material throughout your marking. The Indicative Standard is not intended to be a model answer nor a complete response, and it does not exemplify required content. It is an indication of the quality of response that is typical for each level and shows progression from Level 1 to 4.

Step 1 Determine a level

Start at the lowest level of the mark scheme and use it as a ladder to see whether the answer meets the descriptors for that level. If it meets the lowest level then go to the next one and decide if it meets this level, and so on, until you have a match between the level descriptor and the answer. With practice and familiarity you will be able to quickly skip through the lower levels for better answers. The Indicative Standard column in the mark scheme will help you determine the correct level.

Step 2 Determine a mark

Once you have assigned a level you need to decide on the mark. Balance the range of skills achieved; allow strong performance in some aspects to compensate for others only partially fulfilled. Refer to the standardising scripts to compare standards and allocate a mark accordingly. Re-read as needed to assure yourself that the level and mark are appropriate. An answer which contains nothing of relevance must be awarded no marks.

Advice for Examiners

In fairness to students, all examiners must use the same marking methods.

- Refer constantly to the mark scheme and standardising scripts throughout the marking period.

- Always credit accurate, relevant and appropriate responses that are not necessarily covered by the mark scheme or the standardising scripts.

- Use the full range of marks. Do not hesitate to give full marks if the response merits it.

- Remember the key to accurate and fair marking is consistency.

- If you have any doubt about how to allocate marks to a response, consult your Team Leader.

SECTION A: READING - Assessment Objectives

AO1

- Identify and interpret explicit and implicit information and ideas.

- Select and synthesise evidence from different texts.

AO2

- Explain, comment on and analyse how writers use language and structure to achieve effects and influence readers, using relevant subject terminology to support their views.

AO3

- Compare writers' ideas and perspectives, as well as how these are conveyed, across two or more texts.

AO4

- Evaluate texts critically and support this with appropriate textual references.

SECTION B: WRITING - Assessment Objectives

AO5 (Writing: Content and Organisation)

- Communicate clearly, effectively and imaginatively, selecting and adapting tone, style and register for different forms, purposes and audiences.

- Organise information and ideas, using structural and grammatical features to support coherence and cohesion of texts.

AO6

- Candidates must use a range of vocabulary and sentence structures for clarity, purpose and effect, with accurate spelling and punctuation. (This requirement must constitute 20% of the marks for each specification as a whole).

| Assessment Objective | Section A | Section B |

|---|---|---|

| AO1 | ✓ | |

| AO2 | ✓ | |

| AO3 | N/A | |

| AO4 | ✓ | |

| AO5 | ✓ | |

| AO6 | ✓ |

Answers

Question 1 - Mark Scheme

Read again the first part of the source, from lines 1 to 9. Answer all parts of this question. Choose one answer for each. [4 marks]

Assessment focus (AO1): Identify and interpret explicit and implicit information and ideas. This assesses bullet point 1 (identify and interpret explicit and implicit information and ideas).

- 1.1 What shape is the flower-bed?: oval-shaped – 1 mark

- 1.2 Where were the leaves on the stalks?: half way up – 1 mark

- 1.3 What emerged from the throat?: a straight bar – 1 mark

- 1.4 When the petals moved, what did the red, blue and yellow lights stain?: an inch of the brown earth beneath – 1 mark

Question 2 - Mark Scheme

Look in detail at this extract, from lines 16 to 30 of the source:

16 with a spot of the most intricate colour. The light fell either upon the smooth, grey back of a pebble, or, the shell of a snail with its brown, circular veins, or falling into a raindrop, it expanded

21 with such intensity of red, blue and yellow the thin walls of water that one expected them to burst and disappear. Instead, the drop was left in a second silver grey once more, and the light now settled upon the flesh

26 of a leaf, revealing the branching thread of fibre beneath the surface, and again it moved on and spread its illumination in the vast green spaces beneath the dome

How does the writer use language here to describe the movement of light across the garden? You could include the writer's choice of:

- words and phrases

- language features and techniques

- sentence forms.

[8 marks]

Question 2 (AO2) – Language Analysis (8 marks)

Explain, comment on and analyse how writers use language and structure to achieve effects and influence readers, using relevant subject terminology to support their views. This question assesses language (words, phrases, features, techniques, sentence forms).

Level 4 (Perceptive, detailed analysis) – 7–8 marks Shows perceptive and detailed understanding of language: analyses effects of choices; selects judicious detail; sophisticated and accurate terminology. Indicative Standard: A Level 4 response would perceptively track the personified, fluid motion of light through dynamic verbs — "fell", "expanded", "settled upon", "moved on", "spread its illumination" — noting how the long, cumulative sentence structure echoes its continuous glide. It would also analyse how precise imagery and contrast shape its transformations: the triadic colours "red, blue and yellow" make the drop seem to "burst and disappear" before turning "silver grey once more", while the microscopic focus "revealing the branching thread of fibre" opens out to architectural scale "beneath the dome".

The writer animates the light through personification and dynamic verbs to chart its graceful progress. It "fell upon" one surface, is "falling" in the next clause, then "expanded," before it "settled," "moved on" and finally "spread its illumination." This verb chain, including the present participle "falling," creates a continuous glide, as if the light were a visitor pausing, then proceeding. The noun "illumination" has spiritual connotations, implying the light not only brightens but discloses meaning, while sibilance in "smooth, grey" gives a hushed delicacy.

Moreover, chromatic imagery and hyperbole heighten the sense of pulsating motion. The tricolon of primary colours—"intensity of red, blue and yellow"—builds to a visual crescendo inside the drop. The metaphor "thin walls of water" constructs the raindrop as a fragile chamber so charged that "one expected them to burst and disappear." The adversative adverb "Instead," followed by "silver grey once more," enacts a swift ebb: an expansion and release that mimics the light's fleeting flare and return.

Additionally, the writer shifts from micro to macro through a cumulative sentence and a precise lexical field of anatomy. The light discloses "the flesh of a leaf," its "brown, circular veins," and the "branching thread of fibre," an almost X-ray revelation. Polysyndetic listing ("or... or... and... and...") reproduces the way it glances from pebble to snail to leaf. Finally, "the vast green spaces beneath the dome" extends the image into architectural metaphor, elevating the garden to a cathedral and the light's movement to a reverent, exploratory procession.

Level 3 (Clear, relevant explanation) – 5–6 marks Shows clear understanding; explains effects; relevant detail; clear and accurate terminology. Indicative Standard: A Level 3 response would clearly explain that the writer personifies the light with dynamic verbs like fell, expanded, settled and moved on, and uses vivid colour and close-up imagery such as such intensity of red, blue and yellow and the branching thread of fibre to show its shifting focus. It would also note that the long, flowing, multi-clause sentence and repeated alternatives mirror the light’s smooth sweep from small details to the vast green spaces beneath the dome.

The writer uses dynamic verbs and colour imagery to track the light’s path. The light “fell … upon the smooth, grey back of a pebble” then “expanded” in a raindrop with “red, blue and yellow”, before it “was left … silver grey once more.” These shifting colours show how the light changes whatever it touches, while verbs like “fell,” “expanded” and “settled” suggest a fluid, continuous movement across the garden’s surfaces.

Moreover, personification and metaphor animate this motion. The light “settled upon the flesh of a leaf,” and “revealing the branching thread of fibre,” uses anatomical lexis (“flesh,” “veins”) to make the garden feel alive. The hyperbole that one “expected them to burst and disappear” conveys the energy of the light as it moves, before it “moved on,” implying a brief pause then onward flow.

Furthermore, the long, listing structure (“either … or … or”) and the complex sentence mirror the meandering sweep of light from pebble to snail to raindrop to leaf. Sibilance in “silver grey” and “spread its illumination” creates smoothness, while “beneath the dome” metaphorically frames the garden as a vast space the light crosses. Altogether, these choices clearly convey the graceful, exploratory movement of light across the garden.

Level 2 (Some understanding and comment) – 3–4 marks Attempts to comment on effects; some appropriate detail; some use of terminology. Indicative Standard: The writer uses descriptive words and colour imagery like "smooth, grey back of a pebble" and "red, blue and yellow" to show bright details, and personifies the light with "The light fell" and "settled" as it touches "the flesh of a leaf." The long, flowing sentence with repeated "or" and phrases like "moved on" and "spread its illumination" suggests the light drifting gently from one thing to another across the garden.

The writer uses adjectives and colour imagery to show the light moving across the garden. Phrases like “smooth, grey back” and “brown, circular veins” create a clear picture of where the light lands. The list “red, blue and yellow” shows intensity and changing colours as it passes. The verb “expanded” suggests the light spreads inside the raindrop so it seems to grow.

Furthermore, verbs like “settled” and “moved on” show stages of movement, as if the light pauses then travels. Personification in “spread its illumination” makes the light seem active. The metaphor “flesh of a leaf” and the image of the “branching thread of fibre” show what the light reveals. Additionally, the long, flowing sentence with commas mirrors the continuous movement to the “vast green spaces beneath the dome.”

Level 1 (Simple, limited comment) – 1–2 marks Simple awareness; simple comment; simple references; simple terminology. Indicative Standard: The writer uses colour and describing words like spot of the most intricate colour, smooth, grey back of a pebble, red, blue and yellow, and silver grey to make the light look bright and clear. Simple action words such as fell, expanded, settled, and spread its illumination, and the list of places (pebble, raindrop, leaf), show the light moving gently across the garden.

The writer uses action verbs to show movement of the light, like "fell", "expanded", "settled" and "moved on". This makes the light seem gentle and flowing across the garden. Moreover, the colour words "red, blue and yellow" and the adjective "silver grey" create simple imagery and show changes in the light. Furthermore, the list of objects, "pebble", "snail" and "raindrop", then "leaf", shows the light touching each thing in turn. Additionally, the long sentence with commas and "spread its illumination" makes the movement continuous and makes the garden feel like a "dome".

Level 0 – No marks: Nothing to reward.

AO2 content may include the effects of language features such as:

- Personification makes the light an active traveller, suggesting gentle, purposeful motion from place to place (moved on)

- Polysyndetic listing conveys restless, darting choices as the light touches different surfaces (or falling into a raindrop)

- Vivid primary colour triad intensifies brilliance, evoking prismatic energy within the droplet (red, blue and yellow)

- A structural pivot heightens and then releases tension by overturning the expected bursting (Instead)

- Contrast of chromatic intensity with a return to neutrality presents the momentary, cyclical nature of change (silver grey once more)

- Concrete, tactile detail grounds the sweep of light in varied textures and forms (smooth, grey back)

- Organic metaphor humanises the plant, implying intimacy as light rests on living matter (flesh of a leaf)

- Microscopic precision shows light as revelatory, exposing hidden internal structures (branching thread of fibre)

- Flowing, multi-clausal syntax mirrors the continuous, unbroken glide of illumination (spread its illumination)

- Structural zoom-out enlarges scale from small objects to an overarching canopy, broadening the scene (beneath the dome)

Question 3 - Mark Scheme

You now need to think about the structure of the source as a whole. This text is from the start of a story.

How has the writer structured the text to create a sense of nostalgia?

You could write about:

- how nostalgia deepens by the end of the source

- how the writer uses structure to create an effect

- the writer's use of any other structural features, such as changes in mood, tone or perspective. [8 marks]

Question 3 (AO2) – Structural Analysis (8 marks)

Assesses structure (pivotal point, juxtaposition, flashback, focus shifts, mood/tone, contrast, narrative pace, etc.).

Level 4 (Perceptive, detailed analysis) – 7–8 marks Analyses effects of structural choices; judicious examples; sophisticated terminology. Indicative Standard: Across the whole extract, the writer shifts focus from the impersonal present of From the oval-shaped flower-bed, where the light briefly blooms then returns silver grey, into interleaved memories triggered by Simon’s Fifteen years ago and Eleanor’s For me, a kiss, using this move from external scene to interior recollection to layer past onto present. The recurring dragonfly that went round and round and the final pull back to figures diminished in size... half transparent echo the spoken ghosts lying under the trees, so the structure deepens nostalgia by making moments flare and then fade, like memories briefly illuminated before receding.

One way the writer has structured the text to create a sense of nostalgia is through a gradual shift in focus—a cinematic zoom from impersonal detail to human memory. The opening holds an omniscient lens on colour and light—“the light fell,” “the breeze stirred”—which slows the pace and creates a meditative mood. It pivots when colour is “flashed… into the eyes of the men and women who walk in Kew Gardens in July.” That temporal anchor and generic “men and women” present a recurring summer ritual, priming recollection.

In addition, nostalgia is deepened through analepsis, signalled by temporal references and a shift in focalisation to internal thought: “Fifteen years ago I came here with Lily,” he thought; Eleanor answers with “twenty years ago.” Dialogue—“Tell me, Eleanor”—turns private memory into a shared reflective exchange. A sustained motif of precise fragments—the “square silver buckle,” the “dragonfly” that went “round and round,” “six little girls… painting the water-lilies,” the watch he “marked”—mimics how memory lingers on sensory detail. The anaphora “For me…” juxtaposes parallel reminiscences, universalising nostalgia beyond one life.

A further structural choice is the framed, cyclical ending. After the reminiscences, the perspective pulls back: “They walked on… and soon diminished” until they seem “half transparent” beneath light and shade that “swam” over them. This return to the environmental frame echoes the opening and visually realises Eleanor’s “ghosts lying under the trees.” The shorter clause “They walked on” quickens pace, implying time’s onward motion, so the present itself becomes tinged with loss and the nostalgic tone settles into an elegiac close.

Level 3 (Clear, relevant explanation) – 5–6 marks Explains effects; relevant examples; clear terminology. Indicative Standard: A Level 3 response would explain that the writer structures the piece by shifting focus from detailed description of place (From the oval-shaped flower-bed, with repeated red, blue and yellow) to thoughts and dialogue—signalled by the time marker Fifteen years ago I came here with Lily—so the present scene triggers and deepens nostalgia. It would also note a cyclical return to the setting as they walked on past the flower-bed and become half transparent, echoing ghosts, which makes the past feel closer and the present fade.

One way in which the writer has structured the text to create a sense of nostalgia is the gradual shift in focus from impersonal nature to human memory. The opening lingers on the flower-bed, creating a slow pace, before the focus widens to the “men and women who walk in Kew Gardens in July.” This zoom from petals to people frames the present moment and sets a reflective tone, so the timeless setting naturally prompts recollection.

In addition, the writer uses temporal shifts and a change in perspective to deepen nostalgia. The narrative moves into Simon’s interior thoughts: “Fifteen years ago I came here with Lily,” a clear flashback triggered by the garden. Dialogue sustains the reflective mood (“D’you ever think of the past?”) and the focus then shifts to Eleanor’s memory: “twenty years ago… painting the water-lilies.” This juxtaposition of present walk and past episodes, alongside recurring motifs (the “dragonfly,” the “square silver buckle”), slows the pace and layers shared remembrance.

A further structural feature is the return to the external viewpoint at the end. The family “diminished in size” and became “half transparent,” echoing the earlier “ghosts,” which creates a cyclical frame where the enduring garden contains and outlasts their memories. The final zoom-out leaves a wistful after-image as past and present blur.

Level 2 (Some understanding and comment) – 3–4 marks Attempts to comment; some examples; some terminology. Indicative Standard: The writer moves from detailed setting — From the oval-shaped flower-bed — to personal memories marked by Fifteen years ago and the repeated thought I've been thinking of the past. Ending with the characters diminished in size makes the present feel distant, building a gentle nostalgic mood.

One way the writer structures the text to create a sense of nostalgia is by starting with a slow, detailed opening before shifting focus to the couple. The beginning lingers on "heart-shaped... leaves" and "red, blue and yellow", then moves to "men and women... in July", which gently leads into memory.

In addition, the middle uses a temporal reference and flashback: "Fifteen years ago I came here with Lily." The dialogue ("Do you ever think of the past?") and precise details like the "shoe buckle", "dragonfly" and "a kiss" build a nostalgic mood.

A further structural feature is the ending, which zooms out as they "diminished in size... half transparent." This echoes the earlier "ghosts lying under the trees" and makes them fade like memories, so nostalgia deepens by the end.

Level 1 (Simple, limited comment) – 1–2 marks Simple awareness; simple references; simple terminology. Indicative Standard: The writer starts with the setting of the oval-shaped flower-bed and then shifts to memories like Fifteen years ago I came here with Lily, so it moves from present to past to make it feel nostalgic. By the end, mentions of ghosts lying under the trees and people half transparent show fading, which adds to the nostalgia.

One way the writer creates nostalgia is by starting with the setting. The opening zooms in on flowers and light. This slow beginning creates a calm tone and prepares us for memories.

In addition, the focus shifts to the couple. The time references "Fifteen years ago" and "twenty years ago" act as flashbacks. Their dialogue and thoughts about Lily and the kiss show looking back, which makes a nostalgic mood.

A further feature is the ending. They "walked on" and "diminished in size". This zooms out, and the past feels distant like "ghosts". The nostalgia deepens by the end.

Level 0 – No marks: Nothing to reward.

AO2 content may include the effect of structural features such as:

- Opening close-up on the natural scene slows time and frames a preserved moment, setting a reflective mood for nostalgia (oval-shaped flower-bed)

- Cyclical movement of light and attention creates a pattern of return, mimicking how memories resurface and fade (again it moved)

- A pivot sentence links setting to people, showing the present scene prompting recollection as focus widens to walkers (Then the breeze stirred)

- Simile aligns passers-by with butterflies, structuring the present as fleeting and impressionistic, like sliding, elusive memories (zig-zag flights)

- Focus narrows from crowd to one couple, then slips into interior thought via a clear time-shift, launching a memory sequence (Fifteen years ago)

- Concrete motifs organise recall (dragonfly, shoe), so precise objects anchor the past and intensify longing (square silver buckle)

- Dialogue balances perspectives; parallel reminiscences turn solitary recall into shared nostalgia, broadening the emotional field (a kiss)

- Layered chronology and measured recall present memory as curated and treasured, heightening its value (five minutes only)

- A brief pull back to the present through names and movement contrasts the past’s pull with current roles (Come, Caroline)

- Closing visual dissolve merges figures with the landscape, the present itself fading like a memory (half transparent)

Question 4 - Mark Scheme

For this question focus on the second part of the source, from line 16 to the end.

In this part of the source, Simon links his whole future to where a dragonfly might land, which makes his memory seem a little foolish. The writer suggests that our most important feelings are often attached to small, random details.

To what extent do you agree and/or disagree with this statement?

In your response, you could:

- consider your impressions of Simon linking his future to the dragonfly

- comment on the methods the writer uses to suggest the importance of small details

- support your response with references to the text. [20 marks]

Question 4 (AO4) – Critical Evaluation (20 marks)

Evaluate texts critically and support with appropriate textual references.

Level 4 (Perceptive, detailed evaluation) – 16–20 marks Perceptive ideas; perceptive methods; critical detail on impact; judicious detail. Indicative Standard: A Level 4 response perceptively evaluates the writer’s viewpoint, largely agreeing that profound feelings fix to trivial particulars by showing how Simon places his future in a random sign—'my love, my desire, were in the dragonfly'—yet 'it never settled anywhere', so his hope appears contingent even as 'the whole of her seemed to be in her shoe'. It would analyse narrative method (stream-of-consciousness and symbolism) to compare perspectives, noting Eleanor’s 'For me, a kiss' and Simon’s 'square silver buckle', and arguing that such minutiae crystallise 'one's happiness, one's reality'.

I largely agree with the statement. Woolf presents Simon’s earlier superstition as a little foolish, but only gently so; more importantly, she shows how powerful emotions crystallise around small, contingent details. The writer’s use of free indirect discourse, symbolic imagery and a circling structural motif persuades us that memory clings to minutiae because life itself moves in irregular, chance patterns.

Before Simon speaks, the prose lingers on minute particulars: light “falling into a raindrop” and “expan[ding]” the “thin walls of water” with “red, blue and yellow” before it “was left… silver grey once more.” This sensuous, chromatic imagery repeatedly “settled” and “moved on,” establishing a motif of transience. The camera then tilts to people whose “curiously irregular movement” is likened by simile to “white and blue butterflies” in “zig-zag flights,” embedding human behaviour within randomness. Even the precise measurement that “the man was about six inches in front” is a tiny, concrete detail that signals both his “purposely, though perhaps unconsciously” retreat into thought and the text’s fascination with the small scale.

Within that frame, Simon’s memory dramatises how feeling attaches to trifles. The dragonfly “kept circling,” its motion echoing the earlier zig-zag flight and reinforcing a structural motif of repetition and non-arrival. His analeptic recollection zooms in on Lily’s “shoe with the square silver buckle,” a synecdoche in “the whole of her seemed to be in her shoe,” which compresses an entire person into a gleaming detail. He even displaces “my love, my desire” into the dragonfly, investing it with symbolic agency: the modal conditional “if it settled there” turns chance into an omen. Yet the dash-framed aside—“of course not, happily not”—and the retrospective logic “or I shouldn’t be walking here with Eleanor” temper judgment. The punctuation and self-correction create a tone of gentle irony: the belief was naïve, but recognisably human rather than contemptible.

Eleanor’s counter-memory clinches the second claim. For her, “a kiss… on the back of my neck” from an “old grey-haired woman with a wart on her nose” becomes “the mother of all my kisses,” an incongruous, marginal detail generating lifelong significance. Her meticulous control—she “marked the hour… five minutes only”—shows how a fleeting sensation demands ritual. Finally, as they grow “half transparent” under “large trembling irregular patches” of light and shade, the narrative dissolves them back into the same play of chance. Overall, I agree that Woolf gently exposes Simon’s youthful superstition while persuasively suggesting that our deepest feelings are often anchored to small, random particulars.

Level 3 (Clear, relevant evaluation) – 11–15 marks Clear ideas; clear methods; clear evaluation of impact; relevant references. Indicative Standard: A typical Level 3 response would largely agree, noting that Simon’s hope that if it settled there Lily would accept, followed by it never settled anywhere, makes his memory seem naïve. It would also show how the writer’s focus on tiny images—the square silver shoe buckle and Eleanor’s For me, a kiss timed for five minutes only—suggests intense feelings attach to small, random details.

I mostly agree with the statement. Simon’s memory does risk seeming a little foolish because he links a life-changing decision to “if the dragonfly settled,” yet the writer presents this fixation as a human truth: powerful emotions crystallise around tiny, random details.

Structurally, the passage moves from intense, precise description to personal memory, which supports this idea. The colour imagery and personification of light that “settled upon the flesh of a leaf” and then “flashed into the air” mirror how attention alights on fragments. The simile comparing people’s movement to butterflies’ “zig-zag flights” suggests chance and unpredictability, foreshadowing Simon’s faith in the dragonfly’s circling.

Simon’s interior monologue shows how detail becomes symbolic. He reduces Lily to “her shoe with the square silver buckle,” using metonymy (“the whole of her seemed to be in her shoe”) to show how his mind holds onto a single image to stand for the whole person. The repetition “round and round” for the dragonfly emphasises uncertainty, while the conditional structure “if it settled… she would say ‘Yes’” reveals a superstitious logic. However, the aside “of course not, happily not” complicates the idea of foolishness: he recognises that chance spared him, since he now walks with “Eleanor and the children.” Even the small staging detail that he is “six inches in front” of Eleanor suggests a structural distance: he keeps space to dwell in the past.

Eleanor’s memory confirms the statement. Her hyperbolic metaphor—“the mother of all my kisses”—turns an unlikely, “old grey-haired woman with a wart” into the origin of all future intimacy. Her ritualistic timing (“my watch… five minutes only”) shows how a minor moment governs her feelings. The shared metaphor of “ghosts lying under the trees” universalises this attachment to fragments—“one’s happiness, one’s reality.”

Overall, I agree to a large extent: while Simon’s belief looks naïve, the writer’s imagery, symbolism and shifting viewpoint suggest it is deeply human for our biggest feelings to lodge in the smallest details.

Level 2 (Some evaluation) – 6–10 marks Some understanding; some methods; some evaluative comments; some references. Indicative Standard: I mostly agree, as Simon makes a big decision depend on tiny things like the dragonfly and the square silver buckle, even thinking my love, my desire, were in the dragonfly and waiting for it to land on that leaf, which makes him look a bit foolish. The writer uses simple description and repetition, like the dragonfly going round and round, and Eleanor’s For me, a kiss to show how strong feelings get attached to small, random details.

I mostly agree with the statement. Simon does seem a little foolish when he links his whole future to a dragonfly’s landing, but the writer also shows how feelings cling to tiny details.

At the start, the writer zooms in on small objects with vivid imagery: the light in a “raindrop” that “expanded” into “red, blue and yellow,” and the “branching thread of fibre” in a leaf. This close focus prepares us for Simon’s memory, where a single insect and a “square silver buckle” carry huge meaning. The dragonfly works like a symbol of hope: “if it settled… she would say ‘Yes’.” The repetition in “went round and round: it never settled anywhere” suggests uncertainty and shows it was unrealistic. The precise detail “the whole of her seemed to be in her shoe” shows how he fixes on one small sign to read Lily’s feelings.

I agree that this makes his memory seem naive, even superstitious. However, the tone is not mocking. Simon admits “happily not,” as he is now “walking here with Eleanor and the children,” which softens it and feels human. The idea that feelings attach to details is reinforced by Eleanor’s memory: “For me, a kiss… the kiss of an old grey-haired woman with a wart,” and she even “marked the hour” to think about it. Overall, I agree to a great extent: through imagery, symbolism and the structure from tiny natural details to private memories, the writer shows that small moments can hold our biggest emotions.

Level 1 (Simple, limited) – 1–5 marks Simple ideas; limited methods; simple evaluation; simple references. Indicative Standard: A Level 1 response would mostly agree, saying Simon seems a bit foolish for pinning his future on the dragonfly and fixating on her shoe with the square silver buckle at the toe, while Eleanor remembers For me, a kiss. as the mother of all my kisses all my life. It would simply identify these small details as showing the writer’s idea that strong feelings can rest on little things.

I mostly agree with the statement. Simon does tie his future to where the dragonfly lands, and that makes him seem a little foolish.

The writer shows Simon’s focus on tiny things. He remembers “the dragonfly” going “round and round,” and thinks that if it “settled on the leaf” Lily would say yes. The repetition “round and round” makes the moment feel slow and stuck. He also notices “her shoe with the square silver buckle,” a very small object. This imagery suggests big feelings sit in small sights.

The opening also uses colour, like “red, blue and yellow” in a raindrop and the “flesh of a leaf.” This makes small natural details seem important. Later people are compared to butterflies in “zig-zag flights,” showing how random life and memory are.

Eleanor supports this idea too: she remembers “a kiss… on the back of my neck” and an “old grey-haired woman with a wart,” tiny details linked to strong feelings.

Overall, I agree that big feelings attach to small, random details, and Simon’s belief in the dragonfly seems naïve.

Level 0 – No marks: Nothing to reward. Note: Reference to methods and explicit “I agree/I disagree” may be implicit and still credited according to quality.

AO4 content may include the evaluation of ideas and methods such as:

- Symbolic sign-seeking: Simon ties a life decision to a random natural event, which feels naively superstitious yet recognisably human in its need for signs (if it settled there)

- Circular motion imagery: the insect’s refusal to land sustains futility and suspense, exposing the flaw in basing fate on chance (went round and round)

- Synecdoche/detail focus: a tiny accessory stands for Lily herself, showing how intense feelings fixate on minutiae (square silver buckle)

- Counterfactual acceptance: his retrospective aside reframes the “sign” as a fortunate non-event, complicating any simple judgement of foolishness (happily not)

- Interior monologue/direct address: his self-questioning invites sympathy and nuance, suggesting reflective rather than merely foolish nostalgia (Do you mind my thinking)

- Parallel memory (Eleanor): an unexpected, small sensation becomes a lifelong touchstone, strongly supporting the claim about big feelings and tiny details (mother of all my kisses)

- Measured nostalgia: ritualising recall elevates and contains a fleeting moment, proving how seriously small memories can be curated (marked the hour)

- Universalising metaphor: the garden becomes a repository of shared pasts, implying everyone’s realities cling to minor, passing impressions (ghosts lying under the trees)

- Micro-physical staging: the tiny bodily distance encodes character and priorities, showing how small particulars shape present relationships (six inches in front)

- Dissolving close: their near-transparency under shifting light stresses ephemerality, reinforcing the theme that transient details bear lasting weight (half transparent)

Question 5 - Mark Scheme

To celebrate its anniversary, your local theatre will include creative writing in its next show programme.

Choose one of the options below for your entry.

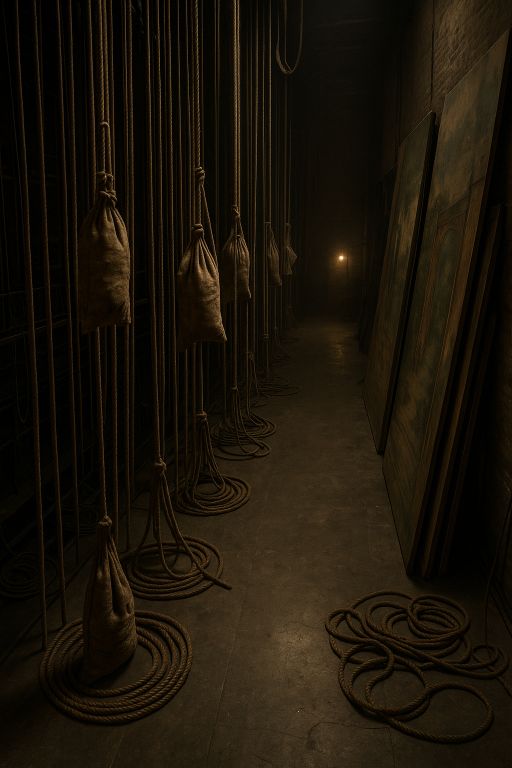

- Option A: Describe a scene backstage at a theatre from your imagination. You may choose to use the picture provided for ideas:

- Option B: Write the opening of a story about a performance that does not go to plan.

(24 marks for content and organisation, 16 marks for technical accuracy) [40 marks]

(24 marks for content and organisation • 16 marks for technical accuracy) [40 marks]

Question 5 (AO5) – Content & Organisation (24 marks)

Communicate clearly, effectively and imaginatively; organise information and ideas to support coherence and cohesion. Levels and typical features follow AQA’s SAMs grid for descriptive/narrative writing. Use the Level 4 → Level 1 descriptors for content and organisation, distinguishing Upper/Lower bands within Levels 4–3–2.

- Level 4 (19–24 marks) Upper 22–24: Convincing and compelling; assured register; extensive and ambitious vocabulary; varied and inventive structure; compelling ideas; fluent paragraphing with seamless discourse markers.

Lower 19–21: Convincing; extensive vocabulary; varied and effective structure; highly engaging with developed complex ideas; consistently coherent paragraphs.

- Level 3 (13–18 marks) Upper 16–18: Consistently clear; register matched; increasingly sophisticated vocabulary and phrasing; effective structural features; engaging, clear connected ideas; coherent paragraphs with integrated markers.

Lower 13–15: Generally clear; vocabulary chosen for effect; usually effective structure; engaging with connected ideas; usually coherent paragraphs.

- Level 2 (7–12 marks) Upper 10–12: Some sustained success; some sustained matching of register/purpose; conscious vocabulary; some devices; some structural features; increasing variety of linked ideas; some paragraphs and markers.

Lower 7–9: Some success; attempts to match register/purpose; attempts to vary vocabulary; attempts structural features; some linked ideas; attempts at paragraphing with markers.

- Level 1 (1–6 marks) Upper 4–6: Simple communication; simple awareness of register/purpose; simple vocabulary/devices; evidence of simple structural features; one or two relevant ideas; random paragraphing.

Lower 1–3: Limited communication; occasional sense of audience/purpose; limited or no structural features; one or two unlinked ideas; no paragraphs.

Level 0: Nothing to reward. NB: If a candidate does not directly address the focus of the task, cap AO5 at 12 (top of Level 2).

Question 5 (AO6) – Technical Accuracy (16 marks)

Students must use a range of vocabulary and sentence structures for clarity, purpose and effect, with accurate spelling and punctuation.

-

Level 4 (13–16): Consistently secure demarcation; wide range of punctuation with high accuracy; full range of sentence forms; secure Standard English and complex grammar; high accuracy in spelling, including ambitious vocabulary; extensive and ambitious vocabulary.

-

Level 3 (9–12): Mostly secure demarcation; range of punctuation mostly successful; variety of sentence forms; mostly appropriate Standard English; generally accurate spelling including complex/irregular words; increasingly sophisticated vocabulary.

-

Level 2 (5–8): Mostly secure demarcation (sometimes accurate); some control of punctuation range; attempts variety of sentence forms; some use of Standard English; some accurate spelling of more complex words; varied vocabulary.

-

Level 1 (1–4): Occasional demarcation; some evidence of conscious punctuation; simple sentence forms; occasional Standard English; accurate basic spelling; simple vocabulary.

-

Level 0: Spelling, punctuation, etc., are sufficiently poor to prevent understanding or meaning.

Model Answers

The following model answers demonstrate both AO5 (Content & Organisation) and AO6 (Technical Accuracy) at each level. Each response shows the expected standard for both assessment objectives.

- Level 4 Upper (22-24 marks for AO5, 13-16 marks for AO6, 35-40 marks total)

Option A:

The wings are a corridor of almost-night; a ribcage of timber and cable where light is rationed into slivers. Dust motes idle in the beam of a work lamp, suspended like forgotten applause. The curtain—its velvet lungs—breathes as the auditorium inhales. Beyond, a thousand strangers rustle their programmes and settle their coats; that soft, tidal expectation presses against the black as insistently as water against a harbour wall. Under the grid, even the air seems to hesitate, tasting of hot dust and paint and the faint, sweet sting of hairspray.

A phalanx of hemp lines hangs in the fly tower, plumb-straight, their fibres polished by years of anxious hands; sandbags squat at their ankles, patient, stubborn weights keeping the sky obedient. Each rope wears a tag that has faded where sweat has fretted at the ink; knots sit like punctuation—commas for pauses, clove hitches for certainty. When a line is tested, the blocks murmur and the timber coughs; the sound is shy, but decisive. The stage floor—scarred, gaffer-taped, cratered with screw holes—is a palimpsest of scuffs and stories; white crosses bloom at exact distances, a quiet geometry of where things must be.

The props table is an altar: tape outlines declare the exact dominion of each object. A chipped teacup, a rubber dagger, a letter sealed with glossy, theatrical blood; a spray of plastic wisteria with leaves that whisper faintly when moved. There is a list, neat and stern and underlined twice. Everything has a place; everything has a cue; everything has a small, passionate history.

At prompt corner, the stage manager perches—headset skewed, pencil behind ear, eyes everywhere—calm, exacting, conspiratorial. The cue lights regard the world in unwavering red. “Stand by, LX twelve; stand by, Sound four; stand by, Fly one and two,” she murmurs into the dark, and the dark murmurs back—Copy. Meanwhile, actors orbit the spill of the lamp in scattered constellations: mouths flexing around consonants, breaths counted, talismans turned in pockets. Someone laughs too brightly and is shushed; someone stares into a cracked mirror and presses colour into cheeks that will be seen as roses from the stalls. The whisper of fabric against fabric is constant, the susurrus of a small forest in wind.

Above, the rig glows with sleeping constellations; gels lie cool as church windows. A rigger braces on a ladder, harness clipped, spanner chiming softly against steel—two turns, a tap, a tug—secure. A flat with a cut-out arch leans, waiting; its casters mutter as it is persuaded to its mark. From the house, the hush thickens; the last cough is swallowed, a phone surrenders to pocketed night. Yet here a dimension of industry persists (the quietest kind of panic): chalk, cue-sheets, whispered arithmetic.

“Stand by—go.” The cue light slips to green; the first bars of music seep like water under a door; the world tilts. Fly one creaks; scenery ascends; weight meets counterweight, up and down, up and down, as sandbags lift and settle with obedient sighs. A single feather escapes a costume and drifts through the beam, deliberate as snow. The tabs peel; a rectangular sunrise pours through the slit, blanching faces into lilies.

And then, almost disappointingly, it simply works: the door opens on its line; the kettle steams when it must; the laugh lands where it should. There is no magic, and there is only magic. Backstage shrugs, resumes its whispered rhythm—ropes breathing, sand settling, the floor drinking spilled light—while the audience stares at the story without ever seeing the hands that make it.

Option B:

Curtains inhale and exhale; the auditorium holds its one, collective breath. Light gathers in the rafters like pollen; dust drifts through the follow-spot’s cone, a million quiet constellations. The stage smells of lemon polish and warm electrics; tape marks criss-cross the floor like a secret map. Somewhere in the gut of the theatre, a pulley whispers. The building itself seems to be listening.

Lena stands in the wings with a pin between her teeth, tasting tin. Her heart is a truculent metronome—too fast, then faster—while her fingers fumble with the vintage brooch she promised her grandmother she would wear. She has recited her opening line so often that the words feel pre-chewed; they are warm in her mouth, crumbly, not quite themselves. “Places!” hisses the stage manager. The word is both command and kindness. Lena steps onto the luminous tape arrow that points towards a life she has practised in fragments. The velvet brushes her shoulder; the curtain is a dormant animal, heavy and patient.

They have rehearsed everything: the pause after the bell, the pocket-watch planted in the desk, the door that sticks on the third knock. Yet, as the overture whispers to a point, the doorbell does not ring. Instead, thunder cracks—thunder, from Act Three—rolling across the ceiling in scandalised waves. The revolve begins to turn and then groans its refusal, leaving the parlour set yawning open to the audience: half wallpapered, half sky blue, a broom like a witness propped in the corner. A bucket glints. Someone backstage says “No—no—no,” but softly, as if afraid to wake the mistake.

Lena’s cue light blinks green. She must go, she must. She slips into the too-bright slab of stage, the heat of the spotlight like a hand on her forehead. The first line evaporates. A thin, inexplicable silence. Her throat shrinks to a tunnel. Then—because air is obstinate and memory is a faithful thing—words return. “Mr Harcourt, you’re early,” she says, and hears at once a whine of feedback. The microphone squeals, then dies, a small, clear betrayal. You can project, she tells herself, you have lungs. She pulls her voice from her ribs and lets it sail. It does not feel elegant; it feels like throwing furniture out of a burning house.

Her scene partner enters through the half-opened revolve and clips a lampshade that swings, an uneasy pendulum. He has the wrong hat on (it belongs to Act Two), and he gives her a look that is apology and accusation and joke. The audience titters, unsure if they’re permitted. She smiles as though this has been ordained, folding chaos into character with a curtsey no one asked for. When her cuff catches on a nail in the doorframe, tearing with a polite little sigh, Lena kneels as if to examine the skirting board, as if this is part of the business. Improvisation, she thinks, is simply courage done quickly.

Meanwhile, the thunder machine continues to mutter its unseasonal rumble. A smoke cue, impatient, releases a pale ribbon that curls around her ankles. The room onstage becomes a misted field—ridiculous, magical, wrong. She chooses a new line, a line not written: “Seems the weather’s followed you indoors, Mr Harcourt.” A beat; then laughter, real and grateful. Relief washes the wings like tide.

It is not the show they drilled into their bones. It is baggier, scuffed, a little breathless; it wears its stitches on the outside. Yet Lena finds, in the oddness, a ferocious concentration. She is suddenly more alive to the exact weight of a porcelain cup, to the itch of wool at her wrist, to a child’s bright face in Row F, mouth open like a door ajar. The plan disintegrates; the story does not. The story, stubborn and shining, decides to go on.

- Level 4 Lower (19-21 marks for AO5, 13-16 marks for AO6, 32-37 marks total)

Option A:

Shadow pools in the wings, thick as velvet, while blades of stage-light slice across ropes and sandbags like a pale tide. The fly lines descend in orderly ranks; their knots are burnished by work and the smell of hemp is grainy and old, like a cupboard of storms. Dust floats in the warm breath of the lamps, and the floor - paint-scuffed by years of shoes - hums with expectation. The curtain holds its breath; so does everyone beside it, learning the pattern of silence.

From prompt corner a small green bulb blinks; a red one holds steady. The deputy stage manager's voice is a calm metronome: "Stand by LX Q28... Sound Q12... Fly, on my 'go'." Headsets hiss; a pencil waits behind an ear. The props table gleams with tape-labelled offerings - goblet, bouquet, sealed letter - each a promise of a world that will exist for exactly three minutes. Gaffer-tape crosses on the deck mark constellations; actors are navigators; the stage is a map that will be folded away before midnight.

A young man stands beneath the rope-labyrinth, lips moving without sound; his fingers rub a ring he does not wear in the scene. Beside him the dresser fastens a hook-and-eye; her hands are quick, almost invisible. Powder smells like school chalk; someone sprays starch, a thin snow on sleeves. From front-of-house a subdued sea-roar rises - programmes rustling, a cough that ricochets - then silences tumble, one upon another, until the quiet is a taut string. "Five minutes, please; five minutes." The call runs along the corridor and resets everyone; someone laughs too brightly, someone swallows. He closes his eyes; his heart is a trapped bird, frantic but not untrained.

Up in the shadowed grid, a rigger leans into his line; the sandbags hang patient as moons. On the deck, a carpenter nudges a flat into place; the false wall shivers, then stands. The lighting operator hovers over a galaxy of faders; colours wait in rows: amber, steel blue, cruel white. The building inhales. "Stand by - go." A drop rises, obedient; the scrape of a revolve is drowned by applause that fountains through the curtain.

Backstage exhales. A whispered joke; a sip of water; a hand on a shoulder. The work continues - quiet, precise, unseen. It is machinery of feeling: ropes, cues, tape, breath, all tugging one way. In the dark, the crew listen for the smallest mistake and take pride when it does not happen. This is the secret pulse of the theatre, steady and stubborn, beating behind the glitter.

Option B:

Curtain. The velvet barrier between rehearsal and reality; a river of red holding back the tide of faces. Behind it, everything hummed: hairspray hung in the air like mist, sequins winked, and the floor, polished to a black lake, reflected our jittering feet. The stage manager’s headset crackled a sibilant lullaby. Somewhere in the audience, a cough ricocheted and was swallowed whole. I breathed to a count of eight and felt my ribs move like bellows. Two minutes on stage. Months of evenings folded into them like a secret note.

“Remember the story, not the steps,” Mrs Porter murmured, smoothing the line of my shoulder with a sculptor’s care. Her smile was steady; mine looked painted on. I pressed rosin to my soles—tap, tap, tap; a ritual to tack me to the world—and touched the blue ribbon on my wrist (Gran’s, talismanic, a whisper of luck). This should be straightforward: music, movement, meaning. What could go wrong? I had practised until the studio mirror fogged with my breath, until the metronome’s click stitched itself into my sleep.

Then the curtain sighed aside and the light found me—white, unblinking, a silent interrogation. The auditorium became a dark ocean of silhouettes. I stepped into the square of brightness and waited for the first piano note, that gentle cascade we’d rehearsed a hundred times. Instead, the speakers erupted with brass: a brash, jubilant fanfare from someone else’s number. The beat slapped the stage; my counts split and skittered like startled birds. Somewhere in the booth, a frantic arm moved; too far and too late. I stood, smiling that not-quite smile, the heat of the lamp prickling my scalp.

Move, I thought. Make it yours. So I broke the first rule and bent the second; I let my body catch the alien rhythm and gave it a softer echo. A turn; a reach; a pivot that pretended to belong. On the second rotation, the ribbon on my right shoe unspooled—a pale snake—licking my ankle. My heel slid. My knee almost kissed the floor. The audience inhaled as one; my heart hammered back in answer, perfectly in time with the wrong music, which would have been funny if it weren’t me.

“Keep going!” Mrs Porter’s voice arrowed from the wing, thin and urgent. The track hiccupped—silence, half a heartbeat—then restarted two bars ahead. A bead of sweat (or panic) ran down my spine. I had a choice: run, or fold the chaos into art. We had never rehearsed this (we never rehearse disaster), but the stage doesn’t care about that.

I lifted my chin. I gathered the trailing ribbon in a fist, transformed it into a silk prop, and raised my other arm as if I’d meant to begin here all along. Breath, count, trust. One, two…

- Level 3 Upper (16-18 marks for AO5, 9-12 marks for AO6, 25-30 marks total)

Option A:

A pale stripe of stage light leaks through the parting velvet, laying a sharp incision across the dust. Ropes hang in ordered curtains; sandbags squat like tired, grey sentries, their seams crusted with chalk. The floor is scuffed and sticky with old tape, a map of past scenes and hurried steps. Somewhere a lamp clicks, hums, settles. The theatre seems to breathe—warm air sighing from vents, the soft exhale of fabric, the distant murmur of an audience that doesn’t know how close it is to all this clutter and care.

Meanwhile, at the prompt desk, a pencil ticks along the margin of a thick, dog-eared book. Cue lights glow—red, then green, then steady; the headset crackles with static and certainty. “House to half,” comes the voice, low and brisk. “Standby LX three; standby flies one to four.” A fingernail taps the stopwatch. They do not look up when someone brushes past, a whisper of tulle and the faint sweetness of hairspray lingering behind. On the props table, outlines have been drawn in tape: a hat, a candlestick, a chipped saucer. Each item sits obediently, waiting to be remembered.

Beyond the wings, actors warm their voices under their breath: a handful of vowels, a clumsy tongue-twister, a half-laughed apology. A dresser moves fast but somehow silent, hands quick with hooks and pins; the sharp, silver smell of safety pins; the powdery fog of make-up that tastes a bit like paper. Shoes are buffed with a sleeve. Someone’s hands tremble. Someone else hums, then stops, then hums again.

Above, the fly tower rises into a dark that feels bottomless. Pulleys groan; the ropes—coarse as old rope should be—slide through calloused palms, and the sandbags lift with patient gravity. They rock slightly, backwards and forwards, backwards and forwards, like a metronome that is almost in time. A batten shifts, a backdrop flutters, and a tiny burst of glitter drifts down like late snow.

“Beginners to the stage, please.” The announcement is calm, but it lands like a drumbeat. The murmur from the auditorium swells; perfume and popcorn drift through the crack in the curtains. A sequin winks from the floor. The red cue light snaps to green. “Standby… and go.”

The velvet moves; the world beyond floods in. For a breath, everything holds—ropes, lungs, notes, nerves. Then the backstage exhales, and the story, bright as it can be, steps out.

Option B:

Evening. The time when the school hall wears its fanciest clothes; plastic chairs in careful rows, programmes folded like fans, a faint murmur of parents and perfume and excitement. The stage waits as if it is holding its breath. On the far wall, the clock ticks too loudly—metronomic, judgemental.

Backstage, my palms are slick against the velvet curtain. It is rougher than I expected, gritty with dust. “Places,” hisses Miss Carter, and the word lands like a pin dropping. I count in fours because it calms me—one, two, three, four—then start again. The script’s first line is tucked into my head where it should be safe; the letter prop, a crucial letter that reveals everything, ought to be safe in my blazer pocket. I pat the fabric anyway. Once. Twice.

“Stand by: lights up,” someone calls. I hear the orchestra of small noises—the pull of ropes, a cough, a shoe squeaking. Somewhere, a child laughs at nothing.

The curtain rises, and light pours over us like warm water. My mouth dries instantly. I step into the room we have built from wood and paint and belief—our living room, our shabby curtains, our lopsided table. My best friend, Ollie, looks at me with his stage-smile. It’s my cue. I open my mouth; my voice remembers its job.

“Father left this for you,” I say, reaching into my pocket for the letter that is the engine of Act One.

My fingers meet nothing. Thin fabric. Air. A slow cold pushes down my spine. I try the other pocket—nothing again. I swallow, the line wouldn’t come. “He—he left… something,” I improvise, which is not the line, not even close. Ollie’s eyes widen a millimetre. From the wings, a white rectangle skitters across the floor like a guilty dove, thrown too late. I lunge, knock the rattling teacups, and one leaps off the saucer—shattering into applause that isn’t applause at all.

Someone in the front row gasps. Someone else laughs because they think it’s part of the show.

“Keep going,” Ollie mutters through his smile. We bend together—two people pretending to pick up a story—and the door flat sticks when he tries to exit. He yanks; the hinge complains; the whole thing comes away in his hand. Another, louder laugh ripples, then catches.

For half a second I consider running. Instead, I stand, cheeks burning, and find a new line. “Our house isn’t what it used to be,” I tell the audience, almost steady now. It isn’t in the script, but they listen. The clock ticks. The stage breathes. We were supposed to be tragic; apparently, we are a comedy tonight.

- Level 3 Lower (13-15 marks for AO5, 9-12 marks for AO6, 22-27 marks total)

Option A:

Behind the black curtain, the world narrows. Ropes hang in straight lines, sandbags crouched like quiet soldiers, their canvas rubbed pale with use. Light leaks in thin slices from the stage; dust swims there, turning. The floor is taped with bright marks that tell you where to stop. It smells of paint and warm metal and something older, a backstage dust that clings to your tongue.

On a cluttered table sit props: a chipped porcelain cup, a fake bouquet, a dagger that shines too clean. Each is tagged with spidery writing. Costumes crowd the rails, sequins winking; sheets of coloured silk whisper when anyone brushes past. People move with careful speed. The stage manager, headset tilted, watches a monitor and a clock at once, murmuring into the mic, counting down; her voice is steady, an anchor in this hidden tide.

Beyond the flats, the audience hums, a sea of coughs and programmes. The orchestra warms up in the pit, stray notes creeping under your skin. Above, the fly lines creak, pulleys talking to each other. A rigger pads by, palms rough with rope fibres; he pats a sandbag as if it were a dog. Heat pools under the lamps. The air is sweet with hairspray and glue, with the faint tang of nervous sweat.

A red bulb blinks in the wing. The understudy flexes her fingers. Then the call comes—Places. For a breath, everything goes still; even the curtain seems to hold itself. A cue light shifts from red to green and a set of flats slides, wheels whispering; floor tape does its job, again and again. A whisper becomes a line, becomes the play. In the shadow, a heart begins to beat.

Option B:

Evening. The school hall hummed with low talk and rustling paper; the air was warm and stifling under the stage lights. Programmes flicked like the wings of small birds, and the red curtain held the smell of dust and leftover paint. Somewhere backstage a cymbal clattered, then stilled, and a baby coughed in the third row.

I rubbed my thumb along the edge of my lyric sheet. The corners had gone soft. Ms Carter squeezed my shoulder and whispered, "You know this, Mia, remember the breath before the first note." Her smile was encouraging, but I could see tightness around her eyes. My guitar strap dug into my neck; the pick I always used was missing, so a new one, too shiny, kept sliding in my fingers. I could hear the murmur of my name from the announcer, stretched and strange.

I stepped into the light. It was whiter than in rehearsal, a clean, blinding circle that erased the edges of the crowd. I found the microphone; it stood too tall, and I fumbled the clip, a clink that sounded huge. Laughs flickered, not cruel, but there.

Breathe. I nodded to Connor at the sound desk. The backing track began, but not mine. An instant wall of drums crashed out of the speakers—something faster, too fast—and the mic shrieked. I winced. The words that were so steady in my room dissolved like sugar in tea. First line, gone. Second line, tangled.

"Start again," someone called, half-kind, half-impatient. My cheeks burned. Ms Carter’s hand rose in the wings, a small wave: carry on. So I did. I hit a chord; it buzzed. My voice came out thin, a thread trying to hold a whole curtain. And somewhere near the front, my little brother lifted the programme over his head like a flag.

- Level 2 Upper (10-12 marks for AO5, 5-8 marks for AO6, 15-20 marks total)

Option A:

The curtain hangs like a dark, heavy wall, hiding the bright stage. In the wings, everything is close: ropes, frames, ladders and the stacked sandbags that slump like tired shoulders. Dust spins in the warm cones of the work lights. There is a smell: paint, hairspray, hot metal from the lanterns, and a faint breath of damp velvet. Beyond us the audience murmurs and coughs like a tide washing the shore; it rises, it falls, then hush.

Meanwhile the stage manager stands with a headset and a creased clipboard. She taps a pencil, she watches the clock. “Five minutes.” The words float down the corridor. A dresser stitches a stubborn seam, quick hands make neat, desperate knots. An actor mouths his lines in the corner as if they were a prayer. Up above, the flyman waits on the platform, a small figure among the ropes; the pulleys answer with a gentle, old creak. On the floor, tape arrows shine pale and bossy, little stars telling us where to land.

Sound crawls around us—boots scuffing, a prop sword clinks, someone laughs too loud and then stops. I feel the heat pressing my back, my palms are damp, my throat dry. The edge of the curtain is frayed, like grass in winter. We wait and listen, wait and listen, wait. A green cue light blinks. “Standby… Standby, and go!” The scene turns, wheels roll, voices swell. For a moment the theatre holds its breath, then we melt into the dark, pushing the story forward.

Option B:

Evening: the time of bright lights; glittering posters; parents with programmes they fold and refold; the air smelling of polish and nerves. In the hall the ceiling hummed with fluorescent tubes, and the stage looked like an open mouth. Someone coughed. I pressed my palms together and tried to stop the tremble, as if my hands were two small birds I could calm. My name was third on the list, which felt both lucky and cruel.

Backstage, Mrs Patel smoothed the curtain and said, 'You’ll be great, Mina,' her voice soft as velvet. I had practiced—after dinner, in the corridor when no one watched; the routine was in my bones, or so I told myself. Sequins scratched my skin. My heart thumped like a drum in the wrong marching rhythm. What could possibly go wrong? I tied my laces twice. I drank a sip of water that tasted of metal; I breathed in, the dust scratched my throat.

Then the music started—only it wasn’t my music. Suddenly the speakers coughed out a heavy bass I didn’t recognise, and the spotlight found me anyway. I stepped on, smiled, tried to bend my mistake into a move. My foot caught the edge of the tape; I slid, arms windmilling like a bad weather vane. A gasp ran through the first row. For a second my mind went blank and bright, like the lights. Mrs Patel mouthed, 'Carry on.' So I did, off-beat, off-plan, making it up. It wasn’t how I imagined, not perfect, but I kept going.

- Level 2 Lower (7-9 marks for AO5, 5-8 marks for AO6, 12-17 marks total)

Option A:

The backstage air is dusty and warm, like breath held for a long time. Ropes hang from the rafters like tired arms; they sway when someone passes. Sandbags squat in rows, heavy and patient, guarding the wings. A slice of light leaks under the velvet curtain, cutting across coils of cable and a scuffed prop trunk. The smell of paint and hot metal mixes with sweat. A hand-written sign says Quiet Please: the walls seem to listen.

Meanwhile the crew move like shadows. A stage manager whispers into a headset, voice crackling, counting down. On the props table, tape, brushes and a dented water bottle wait; someone’s list is taped beside them. A dresser pins a cape to an actor’s shoulder, mouth full of pins, hands quick. In the corner a boy repeats his line again and again until the words sound strange. Backstage is hiding—but it is also busy.

From above comes a small squeak from a pulley, then a thump as a rope settles. Boot steps patter, then stop. The curtain shivers. First a laugh from the audience; then a hush. My heart knocks, even though I’m not on stage. Then the bell rings... Places!

Option B:

The auditorium smelt of polish and nerves. The curtains trembled; so did I. At first, the plan was simple: walk on, smile, count to eight, begin. Miss Carter mouthed break a leg. We had practised the choreography for weeks. A spotlight slid across the floor and the audience was a dark sea.

Firstly, the music skipped. It jumped straight to the chorus, too fast; my careful counts blew away. Suddenly, Ella missed her step and bumped my shoulder, it stung. We tried to recover, arms like windmills, but our angles were wrong. Meanwhile, someone at the back laughed, soft but sharp. My mouth went dry and the smile shook off my face.

I listened for the drum, for a beat, any beat. However, the speaker squealed and the mic on the side whistled. My foot caught on a piece of tape; I slid, not gracefully at all. For a second there was silence—heavy. Then a clap, one, unsure, like a cough. I stood up, cheeks burning, and kept going because stopping felt worse.

- Level 1 Upper (4-6 marks for AO5, 1-4 marks for AO6, 5-10 marks total)

Option A:

Backstage is dark and hot. The ropes was thick and rough, they hang down like old trees in a quiet wood. Sandbags line up on the wall, like sleeping dogs, they dont wake. Dust floats in the thin light, it dances and then it is gone. It smells of paint and sweat and a bit of smoke.

A red bulb watches us, it is tired and small, it means stop. We still move, we slide in and out of the wings, back and forth, back and forth. The floor sticks to my shoes. Tape arrows point like little hands. Its like a secret cave.

People whisper, then someone shouts go, go. A girl in a shiny dress hugs her coat, her makeup shines, her teeth chatter a bit. The prop table are a mess, cups, a fake sword, a feather stuck to gum.

From the stage there is a big noise, like the sea, we all hold our breath.

Option B:

Evening. The time of bright lights, rows of seats, whispering, programmes flipping like small birds. A start for our show. A big start, definately.

As the curtain hung like a heavy blanket, I held my script. My fingers were sweaty and slippery and the paper bent. Miss told us smile, speak loud, breath. The drum went thump and my stomach did to. Stage was shaking, maybe its just me.

I walked out. The spot light hit my face. Hot. White. My mouth opened and my first line hid somewhere far away, like it ran off down the corridor.

Someone coughed. I said Hello? like I was calling a friend, not a prince. Jake whispered, say it, say it now, but nothing came. The mic squealed, horrible and sharp, people jumped.

Then I dropped the plastic sword, it bounced and bounced, and the whole hall laughed: not in the script.

I smiled anyway. We was still on.

- Level 1 Lower (1-3 marks for AO5, 1-4 marks for AO6, 2-7 marks total)

Option A:

Behind the stage it is dark and a bit dusty. There is ropes hanging down like long lines, and big sand bags are tied up and they sway, back and forth, back and forth. A red light glows and makes a small circle on the floor. I hear footsteps and quiet voices, someone says shhh. The floor creaks and a wheel on a box squeeks. Tape on the floor sits in strips, yellow and white. I think of chips later. A jacket is on a chair, it smell of smoke and hair spray. A bell ring and everybody stop and look and wait.

Option B:

The hall is hot. I hold the mic and my hand is wet. The lights feel big and my heart is like a drum, boom boom, but the music dont start and I stand there. We was meant to start at nine, I done the words so many times, I am suppose to breathe slow. I say hello and my voice squeeks and someone laughs, a boy, and the paper slips and fall and hides under the drum. My lace is loose. I think about chips after with mum. The speakers crackle, I try again and the mic switch is off, I forgot it, I press it and everybody is staring.