Mark Scheme

Introduction

The information provided for each question is intended to be a guide to the kind of answers anticipated and is neither exhaustive nor prescriptive. All appropriate responses should be given credit.

Level of response marking instructions

Level of response mark schemes are broken down into four levels (where appropriate). Read through the student's answer and annotate it (as instructed) to show the qualities that are being looked for. You can then award a mark.

You should refer to the standardising material throughout your marking. The Indicative Standard is not intended to be a model answer nor a complete response, and it does not exemplify required content. It is an indication of the quality of response that is typical for each level and shows progression from Level 1 to 4.

Step 1 Determine a level

Start at the lowest level of the mark scheme and use it as a ladder to see whether the answer meets the descriptors for that level. If it meets the lowest level then go to the next one and decide if it meets this level, and so on, until you have a match between the level descriptor and the answer. With practice and familiarity you will be able to quickly skip through the lower levels for better answers. The Indicative Standard column in the mark scheme will help you determine the correct level.

Step 2 Determine a mark

Once you have assigned a level you need to decide on the mark. Balance the range of skills achieved; allow strong performance in some aspects to compensate for others only partially fulfilled. Refer to the standardising scripts to compare standards and allocate a mark accordingly. Re-read as needed to assure yourself that the level and mark are appropriate. An answer which contains nothing of relevance must be awarded no marks.

Advice for Examiners

In fairness to students, all examiners must use the same marking methods.

- Refer constantly to the mark scheme and standardising scripts throughout the marking period.

- Always credit accurate, relevant and appropriate responses that are not necessarily covered by the mark scheme or the standardising scripts.

- Use the full range of marks. Do not hesitate to give full marks if the response merits it.

- Remember the key to accurate and fair marking is consistency.

- If you have any doubt about how to allocate marks to a response, consult your Team Leader.

SECTION A: READING - Assessment Objectives

AO1

- Identify and interpret explicit and implicit information and ideas.

- Select and synthesise evidence from different texts.

AO2

- Explain, comment on and analyse how writers use language and structure to achieve effects and influence readers, using relevant subject terminology to support their views.

AO3

- Compare writers' ideas and perspectives, as well as how these are conveyed, across two or more texts.

AO4

- Evaluate texts critically and support this with appropriate textual references.

SECTION B: WRITING - Assessment Objectives

AO5 (Writing: Content and Organisation)

- Communicate clearly, effectively and imaginatively, selecting and adapting tone, style and register for different forms, purposes and audiences.

- Organise information and ideas, using structural and grammatical features to support coherence and cohesion of texts.

AO6

- Candidates must use a range of vocabulary and sentence structures for clarity, purpose and effect, with accurate spelling and punctuation. (This requirement must constitute 20% of the marks for each specification as a whole).

| Assessment Objective | Section A | Section B |

|---|---|---|

| AO1 | ✓ | |

| AO2 | ✓ | |

| AO3 | N/A | |

| AO4 | ✓ | |

| AO5 | ✓ | |

| AO6 | ✓ |

Answers

Question 1 - Mark Scheme

Read again the first part of the source, from lines 1 to 9. Answer all parts of this question. Choose one answer for each. [4 marks]

Assessment focus (AO1): Identify and interpret explicit and implicit information and ideas. This assesses bullet point 1 (identify and interpret explicit and implicit information and ideas).

- 1.1 How is the pledge described?: hard-wrung – 1 mark

- 1.2 According to the narrator, what pledge has Mrs Reed been forced to make regarding the narrator?: To act in place of a parent to the narrator – 1 mark

- 1.3 According to the narrator, what obligation did Mrs Reed reluctantly accept?: A promise to act in place of a parent to the narrator – 1 mark

- 1.4 According to the narrator, what made the guardian’s role most irksome?: Being bound by a reluctant promise to act as a parent to a child the guardian did not love, and having that child permanently within the family. – 1 mark

Question 2 - Mark Scheme

Look in detail at this extract, from lines 1 to 20 of the source:

1 It must have been most irksome to find herself bound by a hard-wrung pledge to stand in the stead of a parent to a strange child she could not love, and to see an uncongenial alien permanently intruded on her own family group. A singular notion dawned upon me. I doubted not—never doubted—that if Mr. Reed

6 had been alive he would have treated me kindly; and now, as I sat looking at the white bed and overshadowed walls—occasionally also turning a fascinated eye towards the dimly gleaming mirror—I began to recall what I had heard of dead men, troubled in their graves by the violation of their last wishes, revisiting the earth to punish the perjured and avenge the oppressed; and I

11 thought Mr. Reed’s spirit, harassed by the wrongs of his sister’s child, might quit its abode—whether in the church vault or in the unknown world of the departed—and rise before me in this chamber. I wiped my tears and hushed my sobs, fearful lest any sign of violent grief might waken a preternatural voice to comfort me, or elicit from the gloom some haloed face, bending over me with

16 strange pity. This idea, consolatory in theory, I felt would be terrible if realised: with all my might I endeavoured to stifle it—I endeavoured to be firm. Shaking my hair from my eyes, I lifted my head and tried to look boldly round the dark room; at this moment a light gleamed on the wall. Was it, I asked myself, a ray from the moon penetrating some aperture in the blind? No;

How does the writer use language here to describe Jane’s thoughts and feelings as she sits in the red-room? You could include the writer’s choice of:

- words and phrases

- language features and techniques

- sentence forms.

[8 marks]

Question 2 (AO2) – Language Analysis (8 marks)

Explain, comment on and analyse how writers use language and structure to achieve effects and influence readers, using relevant subject terminology to support their views. This question assesses language (words, phrases, features, techniques, sentence forms).

Level 4 (Perceptive, detailed analysis) – 7–8 marks Shows perceptive and detailed understanding of language: analyses effects of choices; selects judicious detail; sophisticated and accurate terminology. Indicative Standard: A Level 4 response would analyse how the writer’s cumulative, multi-clausal syntax and emphatic dashes (the insistence of I doubted not—never doubted—) combine with a charged supernatural lexis (preternatural voice, haloed face) and eerie sensory detail (dimly gleaming mirror) to externalise Jane’s fear and yearning for justice, while the antithesis from consolatory in theory to terrible if realised exposes her conflicted thinking. It would also comment on sentence forms: the sudden image light gleamed triggers self-interrogation (Was it, I asked myself, a ray from the moon … No;), so the shift from long, flowing clauses to clipped denial enacts rising panic despite her attempt at control in I endeavoured to be firm.

The writer initially employs loaded lexis and metaphor to externalise Jane’s conflicted thoughts. The phrase "hard-wrung pledge" foregrounds coercion, while "uncongenial alien" crystallises the way Jane imagines herself as an intrusion; this self-othering makes her feel both guilty and excluded. The metaphor "a singular notion dawned" figures her thought as a faint sunrise in a "white" yet "overshadowed" room, juxtaposing purity with oppression. The "dimly gleaming mirror" adds a Gothic shimmer, hinting that her consciousness is being drawn toward the uncanny.

Moreover, the Gothic semantic field and juridical diction reveal a yearning for protection entwined with fear. References to "dead men... revisiting the earth" and the balanced infinitives "to punish the perjured and avenge the oppressed" give Mr Reed’s spirit a judge-like agency; the polysyllabic lexis suggests moral seriousness, so the reader senses Jane’s desperate appeal to justice. Yet "preternatural voice" and a "haloed face... bending... with strange pity" personify the room’s darkness, making comfort itself frightening.

Furthermore, sentence craft and sound heighten her mounting fear. Parenthetical caesurae—"I doubted not—never doubted—"—perform insistence and self-soothing, while sibilance in "hushed my sobs" and the anaphora "I endeavoured... I endeavoured" enact repression. The antithesis "consolatory in theory... terrible if realised" distils her paradox. Additionally, the clipped interrogative "Was it...?" and abrupt minor "No;" puncture the long, cumulative flow; "gleamed" signals a sudden omen, thrusting the reader into her jolt of terror in the red-room. Thus, Brontë’s language captures Jane’s oscillation between longing and dread in the red-room.

Level 3 (Clear, relevant explanation) – 5–6 marks Shows clear understanding; explains effects; relevant detail; clear and accurate terminology. Indicative Standard: A Level 3 response would explain how Gothic and emotive language conveys Jane’s conflicted fear and hope, citing "wiped my tears and hushed my sobs" and supernatural images like "preternatural voice", "haloed face", and the eerie "dimly gleaming mirror", and noting the contrast "consolatory in theory" yet "terrible if realised". It would also comment on sentence forms: dash-filled asides such as "I doubted not—never doubted—" and repetition in "I endeavoured to stifle it—I endeavoured to be firm" show her struggle for control, while the rhetorical question "Was it, I asked myself...?" builds uncertainty and tension.

The writer uses charged noun phrases to show Jane’s isolation. She imagines Mrs Reed bound by a “hard-wrung pledge” to keep “a strange child,” seeing herself as an “uncongenial alien” “intruded” into the family. This negative lexis makes Jane feel unwanted and explains her anxious, self-blaming thoughts as she sits alone.

Moreover, a Gothic semantic field conveys her fearful imagination. She recalls “dead men… revisiting the earth,” and thinks “Mr. Reed’s spirit… might… rise before me.” The religious imagery of a “haloed face” and the adjective “preternatural” suggest a hope of comfort, yet the juxtaposition “consolatory in theory… terrible if realised” shows conflicted feelings: she longs for protection but is terrified of the supernatural. The metaphor “a singular notion dawned upon me” hints at an idea slowly illuminating her mind amid the darkness of the red-room.

Furthermore, sentence forms and verbs reveal her turmoil. Parenthesis and repetition in “I doubted not—never doubted—” and “—occasionally also turning a fascinated eye—” mimic her nervous, circling thoughts. The triplet of actions “I wiped… hushed… endeavoured” shows efforts to control her distress. Finally, the rhetorical question “Was it… a ray from the moon…? No;” and “gleamed” heighten suspense, capturing her surge of fear.

Level 2 (Some understanding and comment) – 3–4 marks Attempts to comment on effects; some appropriate detail; some use of terminology. Indicative Standard: The writer uses emotive verbs and gloomy imagery to show Jane’s fear, as in I wiped my tears and hushed my sobs, the dimly gleaming mirror and overshadowed walls making the room feel eerie. Supernatural language and a rhetorical question suggest her anxious imagination: a preternatural voice, some haloed face, a light gleamed on the wall, and Was it, I asked myself, a ray from the moon build tension and uncertainty.

The writer uses emotive verbs and adjectives to show Jane’s distress. She “wiped my tears and hushed my sobs”, which suggests she is crying and trying to control herself, making the reader feel sympathy. The description of the “dimly gleaming mirror” and “overshadowed walls” creates eerie imagery and we sense her fear in the red-room.

Furthermore, the writer uses supernatural language: “dead men… revisiting the earth” and “Mr Reed’s spirit… rise before me.” This shows her imagination running wild, so she is both comforted and scared. The contrast “consolatory in theory… terrible if realised” reveals confused feelings.

Moreover, repetition shows anxious thoughts: “I doubted not—never doubted” emphasises her certainty about Mr Reed’s kindness, while the dashes suggest a restless mind.

Additionally, a rhetorical question builds tension: “Was it… a ray from the moon?” and the verb “gleamed” shows her curiosity as she tries to look “boldly” brave.

Level 1 (Simple, limited comment) – 1–2 marks Simple awareness; simple comment; simple references; simple terminology. Indicative Standard: The writer uses simple emotive words like 'tears' and 'sobs' to show Jane is upset and scared, and spooky words like 'dead men', 'spirit' and 'gloom' to create a creepy mood. A rhetorical question starting with 'Was it' and the phrase 'a light gleamed on the wall' in the 'dark room' show her fear and uncertainty.

The writer uses emotive language to show Jane’s fear in the red-room. Words like “fearful,” “violent grief,” and “terrible if realised” make her seem very scared and tense. Moreover, ghostly imagery is used: “dead men… revisiting the earth,” “Mr Reed’s spirit… rise before me,” and a “preternatural voice” and “haloed face.” This suggests her thoughts are full of supernatural ideas, making the room feel haunted. Furthermore, the rhetorical question “Was it…?” and the abrupt “No;” show doubt. The repetition “I doubted not—never doubted—” shows her clinging to comfort.

Level 0 – No marks: Nothing to reward.

AO2 content may include the effects of language features such as:

- Emotive lexis presents her as an unloved burden, heightening isolation (most irksome)

- Dehumanising noun phrase intensifies her outsider status and permanent exclusion (uncongenial alien)

- Repetition with dashes shows absolute, yearning certainty about lost protection, revealing need for kindness (never doubted)

- Eerie setting imagery blends purity and shadow, mirroring her mixed fascination and fear (dimly gleaming)

- Moral, justice-charged parallelism frames her as wronged, fusing fear with a desire for redress (avenge the oppressed)

- Modal uncertainty and speculative options build anxious, superstitious anticipation (unknown world)

- Supernatural lexis marks comfort as frighteningly other, revealing conflicted longing for aid (preternatural voice)

- Concrete self-soothing actions show vulnerability and her attempt to control overwhelming emotion (hushed my sobs)

- Antithesis captures her conflicted mind: imagined comfort would in reality terrify (terrible if realised)

- Sudden image and rhetorical question, cut off by the abrupt denial, escalate suspense and panic (a light gleamed)

Question 3 - Mark Scheme

You now need to think about the structure of the source as a whole. This text is from the start of a novel.

How has the writer structured the text to create a sense of claustrophobia?

You could write about:

- how claustrophobia intensifies from beginning to end

- how the writer uses structure to create an effect

- the writer's use of any other structural features, such as changes in mood, tone or perspective. [8 marks]

Question 3 (AO2) – Structural Analysis (8 marks)

Assesses structure (pivotal point, juxtaposition, flashback, focus shifts, mood/tone, contrast, narrative pace, etc.).

Level 4 (Perceptive, detailed analysis) – 7–8 marks Analyses effects of structural choices; judicious examples; sophisticated terminology. Indicative Standard: A Level 4 response would perceptively track how the structure tightens enclosure, moving from a static, boxed-in frame on the white bed and overshadowed walls and the dimly gleaming mirror, through the encroaching light that glided up to the ceiling and quivered over my head, to breathless cumulative clauses where the narrator is oppressed, suffocated. It would also analyse the pivot from introspection to frantic action and an ironic clampdown—although she rushed to the door and shook the lock, Mrs. Reed locked me in, and the final line unconsciousness closed the scene seals the claustrophobia.

One way the writer structures the text to create claustrophobia is by narrowing focus from abstract grievance to the enclosed room. We open with ideas about pledges and Mr Reed; swiftly the focalisation tightens to "the white bed and overshadowed walls" and the "dimly gleaming mirror". The viewpoint then tracks a "light" as it "glided up to the ceiling and quivered over my head". This spatial zoom from thought to surfaces pins the gaze to walls and ceiling, compressing the space and confining the reader with the narrator.

In addition, a structural pivot accelerates the narrative pace to intensify pressure. The "streak of light" functions as a volta; afterwards action comes in rapid, sequential clauses: "My heart beat thick... I rushed to the door and shook the lock." Threshold motifs—"door", "lock", "key turned"—organise the scene as an obstacle course. Even when "Bessie and Abbot entered", opening becomes intrusion, not release. This accelerando creates a breathless rhythm, mirroring "oppressed, suffocated" sensations and enclosing the reader in her panic.

A further structural feature is the shift from interior monologue to authoritative dialogue, which tightens confinement temporally and socially. A retrospective aside—"I can now conjecture readily"—widens perspective before Mrs Reed’s imperatives clamp down: "you will... stay here an hour longer... only on condition". The passage is framed by an entrapment motif, opening with "bound... pledge" and closing with "locked me in" and "unconsciousness closed the scene". This cyclical framing seals the extract, claustrophobia escalates from imagined to literal imprisonment.

Level 3 (Clear, relevant explanation) – 5–6 marks Explains effects; relevant examples; clear terminology. Indicative Standard: A Level 3 response would clearly track how claustrophobia intensifies through structural shifts—from introspective unease ('A singular notion dawned upon me', focus on 'white bed and overshadowed walls') and the unsettling light ('it glided up to the ceiling and quivered over my head'), to a climactic struggle ('rushed to the door and shook the lock') interrupted by controlling dialogue ('another voice peremptorily', 'you will now stay here an hour longer'), ending with final enclosure ('locked me in', 'unconsciousness closed the scene')—explaining how each stage narrows space and agency.

One way in which the writer structures the extract to create claustrophobia is by narrowing the narrative focus from the wider situation to the enclosed room and then to Jane’s body. The perspective shifts from reflective to intensely localised, zooming in on “the white bed and overshadowed walls” and the “dimly gleaming mirror,” which confines our view to boxed-in objects. Temporal markers like “at this moment” and “while I gazed” tighten the pacing as the light “glided up to the ceiling,” seeming to close the space above her and press the room inwards.

In addition, there is a clear shift from interior narration to intrusive dialogue, which crowds the scene. The sudden action—“Steps came running… the key turned”—moves the focus to multiple voices in rapid succession. This change in mode accelerates the pace and creates a crush of sound: Jane’s plea, “Take me out!” is immediately opposed by Mrs Reed’s imperatives, “Let her go… you will now stay here an hour longer.” The juxtaposition of hoped release with renewed restraint intensifies the sense of entrapment.

A further structural choice is the build to a climax and sealed ending. The sequence escalates to Jane being “abruptly thrust… back” and re-locked, and the final line—“unconsciousness closed the scene”—provides a hard closure, reinforcing a suffocating lack of escape.

Level 2 (Some understanding and comment) – 3–4 marks Attempts to comment; some examples; some terminology. Indicative Standard: A Level 2 response would note that the writer starts with a confined setting (the white bed and overshadowed walls), then shifts to the moving light that glided up to the ceiling, and finishes with panicky action and authority, using phrases like oppressed, suffocated and locked me in to show the claustrophobia building.

One way the writer creates claustrophobia is through the opening focus on the confined setting. At the beginning, the first-person narrator looks at the “white bed” and “overshadowed walls” and the “dimly gleaming mirror.” This tight, indoor focus and single perspective keep us inside the room, so the reader feels boxed in with her.

In addition, the middle shifts focus and pace. The moving light “glided” and “quivered,” then a rapid series of actions follows: “my heart beat,” “I was oppressed, suffocated,” “I rushed to the door and shook the lock.” This quickening pace and the locked door as a barrier increase the sense of being trapped.

A further structural feature is the ending. Although others enter, authority closes down escape: “you will now stay here an hour longer,” and Mrs Reed “locked me in.” The final line, “unconsciousness closed the scene,” gives a closed ending, tightening the claustrophobia.

Level 1 (Simple, limited comment) – 1–2 marks Simple awareness; simple references; simple terminology. Indicative Standard: It starts with quiet details like the "white bed" and "overshadowed walls", then builds to panic when she "rushed to the door and shook the lock". With "Steps came running", "the key turned", and being "locked me in" in "the red- room", the structure makes it feel trapped and claustrophobic.

One way the writer structures the text to create claustrophobia is by starting with a close focus on the room. At the beginning she looks at the bed, walls and mirror, which feels closed in.

In addition, the middle speeds up with short sentences and actions like 'My heart beat thick' and 'I rushed to the door.' This pace builds panic and makes the space tighter and scarier.

A further structural point is the ending, where dialogue and 'an hour longer' keep her inside. Being locked in at the end, in first person, leaves the reader stuck with her.

Level 0 – No marks: Nothing to reward.

AO2 content may include the effect of structural features such as:

- Opening frames social imprisonment (duty, intrusion) → establishes a baseline of constraint that primes the scene’s confinement (bound by a hard-wrung pledge).

- Narrow focalisation on enclosed objects → visual boundaries compress space and attention within the room (white bed and overshadowed walls).

- Escalation from rational memory to spectral possibility → imagined presence invades the same space, tightening mental enclosure (rise before me in this chamber).

- Structural pivot with a moving light and self-questioning → uncertainty loops inside the room, heightening entrapment (a light gleamed on the wall).

- The light’s path across surfaces caps the space → ceiling-tracking imagery presses down from above (glided up to the ceiling).

- Retrospective aside interrupts to offer reason → contrast with immediate terror deepens the sense of being trapped in the moment (I can now conjecture readily).

- Climactic sensory pile-up in brief, paratactic clauses → breathless rhythm creates bodily suffocation (oppressed, suffocated).

- Action beats against a barrier → failed escape externalises confinement through the locked door (shook the lock).

- Shift to crowded dialogue and command → brief hope turns to tighter control as authority extends the confinement (you will now stay here).

- Final re-isolation and blackout → closing line seals the enclosure with a definitive shutdown (closed the scene).

Question 4 - Mark Scheme

For this question focus on the second part of the source, from line 16 to the end.

In this part of the source, where Mrs Reed dismisses Jane’s screams as ‘tricks’, her cruelty seems extreme. The writer suggests that Mrs Reed genuinely sees Jane as a liar rather than a terrified child.

To what extent do you agree and/or disagree with this statement?

In your response, you could:

- consider your impressions of Mrs Reed's harsh treatment of Jane

- comment on the methods the writer uses to present Mrs Reed's view of Jane

- support your response with references to the text. [20 marks]

Question 4 (AO4) – Critical Evaluation (20 marks)

Evaluate texts critically and support with appropriate textual references.

Level 4 (Perceptive, detailed evaluation) – 16–20 marks Perceptive ideas; perceptive methods; critical detail on impact; judicious detail. Indicative Standard: A Level 4 response would argue that Brontë frames Mrs Reed as sincerely construing Jane as deceitful—“I abhor artifice,” “it is my duty to show you that tricks will not answer,” and the retrospective “I was a precocious actress in her eyes” and “dangerous duplicity”—while juxtaposing this with Jane’s palpable terror and victimisation (“frantic anguish,” “abruptly thrust me back”) to judge the extremity of her cruelty. It would largely agree, evaluating how imperious diction (“Silence!,” “repulsive,” cap flying wide, gown rustling stormily) and the retrospective narrative voice construct Mrs Reed’s viewpoint and invite reader condemnation.

I largely agree that Mrs Reed’s cruelty seems extreme, and that the writer suggests she sincerely misreads Jane as deceitful rather than terrified. Brontë first establishes the authenticity of Jane’s fear through intense sensory and figurative detail so that any dismissal as “tricks” feels grossly unjust. The light “glided up to the ceiling and quivered,” a personifying image that, coupled with the retrospective aside “I can now conjecture,” contrasts adult reason with childlike dread. The asyndetic accumulation “My heart beat thick, my head grew hot; a sound filled my ears… I was oppressed, suffocated” foregrounds genuine panic. Structurally, the shift from internal terror to frantic action—“I rushed to the door and shook the lock”—renders the scream an involuntary eruption, not calculated “artifice.”

The subsequent dialogue frames the competing adult responses. Bessie’s hand, which “she did not snatch… from me,” and her “pleaded” tone momentarily validate Jane’s distress. By contrast, Abbot’s adverbials signal cold contempt: she speaks “in some disgust” and asserts “I know her naughty tricks.” This direct speech plants the semantic field of deceit—“tricks,” “on purpose”—that Mrs Reed will amplify. The reader, already aligned to Jane’s focalised fear, is prompted to evaluate such accusations as wilful misinterpretation, heightening the sense of cruelty.

When Mrs Reed enters, her authoritarian presence is aurally and visually forceful: “peremptorily,” with “her gown rustling stormily.” The stormy auditory image externalises her implacability. Her lexis is moralising and absolute—“I abhor artifice,” “It is my duty,” “perfect submission and stillness”—and the imperative mood (“Let her go,” “Loose Bessie’s hand,” “Silence!”) enacts punishment rather than care. Crucially, the narrator’s retrospective comment clinches the statement’s claim: “and so, no doubt, she felt it… she sincerely looked on me as a compound of virulent passions, mean spirit, and dangerous duplicity.” The adverb “sincerely” and the loaded triadic catalogue “virulent… mean… dangerous” show Mrs Reed genuinely believes Jane is a liar, even an embryonic moral threat. That conviction makes the cruelty more chilling: she “abruptly thrust me back and locked me in,” a pair of harsh dynamic verbs culminating in the child’s “species of fit.” Structurally, the scene closes on unconsciousness, underscoring the extreme, bodily consequences of misjudged discipline.

Overall, I agree to a great extent: Brontë constructs a persuasive portrait of a terrified child and an adult who, under the banner of “duty,” misreads fear as duplicity. The sincerity of Mrs Reed’s belief does not mitigate but intensifies the extremity of her cruelty.

Level 3 (Clear, relevant evaluation) – 11–15 marks Clear ideas; clear methods; clear evaluation of impact; relevant references. Indicative Standard: A typical Level 3 response would largely agree, explaining that through dialogue and narrative comment the writer shows Mrs Reed genuinely believes Jane is deceitful: she condemns her as using tricks, declares I abhor artifice, views her as a precocious actress with dangerous duplicity, and justifies punishment as it is my duty. It would contrast this with Jane’s obvious terror—I thought a ghost would come, frantic anguish—to judge the cruelty as extreme.

I agree to a large extent. In this section, the writer presents Jane as a genuinely terrified child, while Mrs Reed’s responses, grounded in her belief in “tricks,” seem extremely harsh.

The first-person narrative immerses us in Jane’s fear through sensory imagery and dynamic verbs. The light “glided up to the ceiling and quivered,” a metaphorical, almost supernatural movement that feeds her panic. The auditory and physical imagery—“a sound… the rushing of wings,” “I was oppressed, suffocated”—positions the reader inside her terror before she “rushed to the door and shook the lock in desperate effort.” Although the narrator later coolly reflects, “I can now conjecture” it was a lantern, this retrospective aside contrasts with the immediate, childlike dread, intensifying our sense that adult dismissal is unjust.

Dialogue and description shape Mrs Reed’s viewpoint. Even before she speaks, the adverb “peremptorily” and the vivid detail “her cap flying wide, her gown rustling stormily” create a tone of domineering authority. Her word choices belong to a semantic field of deceit: “I abhor artifice… tricks will not answer.” The imperatives—“Let her go… Loose Bessie’s hand… you will now stay”—shut down Jane’s plea for “pity,” presenting Mrs Reed as unyielding. Crucially, the narrative comment “she sincerely looked on me as a compound of virulent passions, mean spirit, and dangerous duplicity” uses the adverb “sincerely” to confirm she truly believes Jane is a liar, not frightened. The triadic list of condemnatory nouns exaggerates her misjudgment.

Finally, Mrs Reed’s actions escalate the cruelty. The adverb and verb in “abruptly thrust me back and locked me in” suggest physical force and emotional coldness; structurally, this leads directly to Jane’s “species of fit,” showing real harm caused by disbelief.

Overall, I strongly agree: the writer contrasts vivid childlike terror with authoritarian, moralising language to present Mrs Reed’s cruelty as extreme, and to show she genuinely misreads Jane as deceitful rather than afraid.

Level 2 (Some evaluation) – 6–10 marks Some understanding; some methods; some evaluative comments; some references. Indicative Standard: A Level 2 response would mostly agree that the writer suggests Mrs Reed genuinely sees Jane as deceitful, using straightforward quotes like "tricks", "I abhor artifice", "she sincerely looked on me" and "dangerous duplicity" to show belief in lies rather than fear. It would also identify her cruelty with basic evidence such as "abruptly thrust me back" and "locked me in", with limited explanation of effect.

In this part of the source, I mostly agree that Mrs Reed’s cruelty seems extreme and that she truly thinks Jane is lying rather than frightened. The writer first shows Jane’s real terror through the first person description: the “light… glided up to the ceiling” and she feels “oppressed, suffocated”. Phrases like “my heart beat thick” and “I rushed to the door” make her panic believable. This builds sympathy and suggests her screams are not “tricks”. Even Bessie holds her hand, which contrasts with Abbot’s “disgust”.

When the adults arrive, dialogue and description present Mrs Reed as harsh. Abbot already calls them “naughty tricks”, and then Mrs Reed enters “peremptorily”, with her gown “rustling stormily”. These adjectives and adverbs make her seem angry. Her direct speech, “I abhor artifice… tricks will not answer,” shows she genuinely believes Jane is deceitful. She ignores Jane’s plea, “O aunt! have pity!” and instead orders “Silence!” “She sincerely looked on me as a compound of… dangerous duplicity,” “sincerely” confirming Mrs Reed truly sees Jane as a liar.

Finally, the strong verbs “abruptly thrust me back and locked me in” show physical force and a lack of care. The effect on Jane is severe: “a species of fit… unconsciousness,” which makes Mrs Reed’s punishment feel more cruel because it harms a terrified child.

Overall, I agree to a large extent. The writer uses description and dialogue to present Mrs Reed as unkind and convinced that Jane is acting, not suffering.

Level 1 (Simple, limited) – 1–5 marks Simple ideas; limited methods; simple evaluation; simple references. Indicative Standard: A Level 1 response would mostly agree, noticing that Mrs Reed says I abhor artifice and tricks will not answer, so she sees Jane as lying. It might also mention her cruelty when she locked me in despite Jane’s frantic anguish.

I mostly agree with the statement. Jane is clearly terrified. She sees “a light” that “glided up to the ceiling” and hears “the rushing of wings”. This sensory language shows panic, so her screams are not just “tricks”. When the servants come, Abbot calls them “naughty tricks”. Then Mrs Reed arrives “peremptorily” with her “gown rustling stormily”. In her dialogue she says, “I abhor artifice” and “tricks will not answer.” This choice of words shows she believes Jane is pretending. The narrator also comments, “I was a precocious actress in her eyes”; Mrs Reed “sincerely looked on me as… dangerous duplicity.” Her actions are harsh too: she “abruptly thrust me back and locked me in”. The strong verb “thrust” shows cruelty. Overall, I agree that Mrs Reed sees Jane as a liar rather than a frightened child, and this makes her behaviour seem extremely cruel.

Level 0 – No marks: Nothing to reward. Note: Reference to methods and explicit “I agree/I disagree” may be implicit and still credited according to quality.

AO4 content may include the evaluation of ideas and methods such as:

- Sensory and supernatural imagery foregrounds Jane’s genuine terror, heightening the perceived cruelty of dismissal (I thought a ghost would come).

- Other adults frame Jane as deceitful from the outset, priming the reader to weigh Mrs Reed’s stance critically (naughty tricks).

- Stage directions and sound convey authoritarian severity, encouraging a judgment of harshness (gown rustling stormily).

- Imperatives reframe comfort as manipulation, showing Mrs Reed’s assumption that Jane is scheming rather than scared (Loose Bessie's hand).

- Lexis of deceit makes her verdict explicit, suggesting she truly interprets Jane’s distress as calculated (I abhor artifice).

- Moral justification positions punishment as righteous duty, implying sincere belief rather than mere spite (it is my duty).

- Narratorial aside confirms her conviction, supporting the idea that she genuinely misreads Jane’s motives (she sincerely looked on me).

- Intensified character judgment casts Jane as inherently untrustworthy, reinforcing the “liar” reading (dangerous duplicity).

- Physical force escalates the response beyond reason, rendering her treatment extreme in the face of a child’s panic (abruptly thrust me back).

- The collapse into unconsciousness underlines authentic fear, challenging the “tricks” label and magnifying Mrs Reed’s misjudgment (species of fit).

Question 5 - Mark Scheme

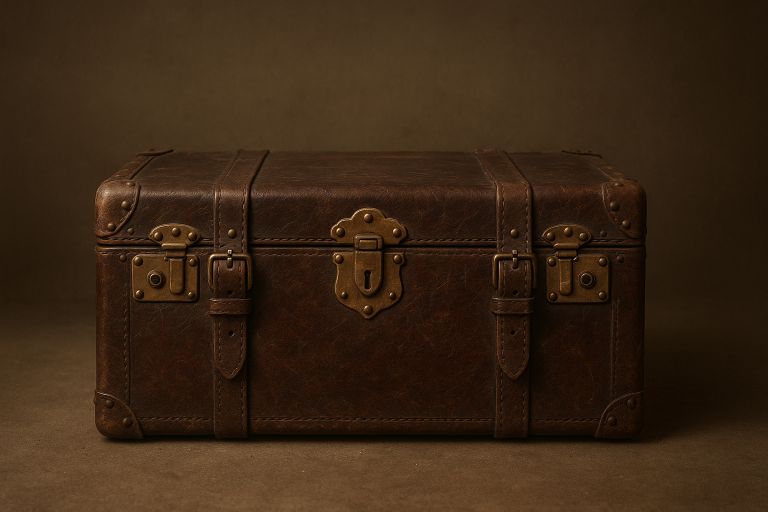

The town museum is preparing an exhibition around a mysterious, locked trunk and has invited creative writing for the display.

Choose one of the options below for your entry.

- Option A: Describe an object that holds a secret from your imagination. You may choose to use the picture provided for ideas:

- Option B: Write the opening of a story about a discovery that starts a search.

(24 marks for content and organisation, 16 marks for technical accuracy) [40 marks]

(24 marks for content and organisation • 16 marks for technical accuracy) [40 marks]

Question 5 (AO5) – Content & Organisation (24 marks)

Communicate clearly, effectively and imaginatively; organise information and ideas to support coherence and cohesion. Levels and typical features follow AQA’s SAMs grid for descriptive/narrative writing. Use the Level 4 → Level 1 descriptors for content and organisation, distinguishing Upper/Lower bands within Levels 4–3–2.

- Level 4 (19–24 marks) Upper 22–24: Convincing and compelling; assured register; extensive and ambitious vocabulary; varied and inventive structure; compelling ideas; fluent paragraphing with seamless discourse markers.

Lower 19–21: Convincing; extensive vocabulary; varied and effective structure; highly engaging with developed complex ideas; consistently coherent paragraphs.

- Level 3 (13–18 marks) Upper 16–18: Consistently clear; register matched; increasingly sophisticated vocabulary and phrasing; effective structural features; engaging, clear connected ideas; coherent paragraphs with integrated markers.

Lower 13–15: Generally clear; vocabulary chosen for effect; usually effective structure; engaging with connected ideas; usually coherent paragraphs.

- Level 2 (7–12 marks) Upper 10–12: Some sustained success; some sustained matching of register/purpose; conscious vocabulary; some devices; some structural features; increasing variety of linked ideas; some paragraphs and markers.

Lower 7–9: Some success; attempts to match register/purpose; attempts to vary vocabulary; attempts structural features; some linked ideas; attempts at paragraphing with markers.

- Level 1 (1–6 marks) Upper 4–6: Simple communication; simple awareness of register/purpose; simple vocabulary/devices; evidence of simple structural features; one or two relevant ideas; random paragraphing.

Lower 1–3: Limited communication; occasional sense of audience/purpose; limited or no structural features; one or two unlinked ideas; no paragraphs.

Level 0: Nothing to reward. NB: If a candidate does not directly address the focus of the task, cap AO5 at 12 (top of Level 2).

Question 5 (AO6) – Technical Accuracy (16 marks)

Students must use a range of vocabulary and sentence structures for clarity, purpose and effect, with accurate spelling and punctuation.

-

Level 4 (13–16): Consistently secure demarcation; wide range of punctuation with high accuracy; full range of sentence forms; secure Standard English and complex grammar; high accuracy in spelling, including ambitious vocabulary; extensive and ambitious vocabulary.

-

Level 3 (9–12): Mostly secure demarcation; range of punctuation mostly successful; variety of sentence forms; mostly appropriate Standard English; generally accurate spelling including complex/irregular words; increasingly sophisticated vocabulary.

-

Level 2 (5–8): Mostly secure demarcation (sometimes accurate); some control of punctuation range; attempts variety of sentence forms; some use of Standard English; some accurate spelling of more complex words; varied vocabulary.

-

Level 1 (1–4): Occasional demarcation; some evidence of conscious punctuation; simple sentence forms; occasional Standard English; accurate basic spelling; simple vocabulary.

-

Level 0: Spelling, punctuation, etc., are sufficiently poor to prevent understanding or meaning.

Model Answers

The following model answers demonstrate both AO5 (Content & Organisation) and AO6 (Technical Accuracy) at each level. Each response shows the expected standard for both assessment objectives.

- Level 4 Upper (22-24 marks for AO5, 13-16 marks for AO6, 35-40 marks total)

Option A:

Under the sloped roof, in a net of dusty light, the leather trunk keeps its counsel. Its hide, once swaggering, is now a palimpsest of creases and scars; the grain has blackened into tributaries, a geography people used to read with their hands. Brass corners bloom with verdigris; nails dot the edges like constellations. Straps lie across it like tamed snakes—cracked, obedient, intransigent nevertheless. The air around it tastes faintly of salt and beeswax, of forgotten rooms; pertinently, the trunk remembers.

Press your palm to the lid and the dust gives, soft as ash. Underneath, the leather is dense, oddly warm, and stubbornly alive; it resists the way seasoned wood resists, having learned the art of saying no. The keyhole stares like a single iron pupil, glossy with use, blind with waiting. Sometimes—though it may be the eaves rehearsing their winter—there is a susurrus in its seams, a breath caught and folded back.

Three locks rule its lip, a triptych of refusal. When I test them, the metal answers in cramped syllables: click, clack; click, clack; a metronome of negation. The keys are gone, of course; secrets prefer absences to answers.

What could it hold? Not linens, not the pedestrian cargo of house-moves and spring-cleans. Perhaps it cradles a bottled storm—sea glassed and stoppered—trembling if your voice turns too bright. Or a letter that edits itself as you read; a map that redraws the road beneath your feet. Alternatively, something smaller: a single name, brittle as an autumn leaf, that someone once could not bear to say aloud.

It is more creature than furniture. Rivets are knuckles; the lid is a ribcage bound down by straps; the hinges, a spine that refuses to bow. It has the patient weight of an animal hibernating, the faintly sweet musk of old fur.

Around it, the attic continues its quiet industry: beams tick as they cool; a sparrow skitters along the tiles; light sifts itself into visible dust, slow and deliberate. The world below is brisk, ringing with appointments. Up here, the clock goes elsewhere.

I slide a cautious nail under the seam and feel the minuscule give, an intake of breath that might be mine. The lid does not lift; the trunk is politely, perfectly intransigent. A splinter flowers in my thumb—small, instructive, bright—and I put my hand back on the leather instead, as if calming a horse. What would it change, to pry?

So I leave it closed: for later; for braver weather; for the key that is perhaps not metal at all. The secret inside remains heavier than wood, lighter than dust, older than both. Still, the locks gleam a little, as if pleased to have kept their counsel again, and the trunk—ordinary, obstinate—continues to hold whatever it holds.

Option B:

Autumn. A season when the trees practise letting go; our house, contrariwise, clung. Dust held on to beams like a stubborn thought, and the air was redolent of camphor, old paper and something sweetly metallic, as if a song had rusted in the rafters. Light slipped through the small attic window and puddled on the boards, tentative and pale, revealing a palimpsest of footprints—mine overlaying older, almost faded steps.

“Are you nearly done?” Mum’s voice rose through the hatch like steam.

“Two minutes!” I lied, because the attic had started talking to me in a way I could not ignore: a sibilant whisper in the insulation, a quiet urging beneath the itch of dust. My fingers traced the outline of a loose plank, the wood warming under my palm. When I prised it up, careful as a dentist, a cloud of desiccated moth wings drifted; then something small and tinny skittered out, hit my ankle and came to rest against the skirting as if relieved.

It was a biscuit tin, blue once, now the exact colour of rain that has given up. Its lid held a filigree of scratches, a constellation of accidents. Inside—after a breath and a stupid, ceremonial count of three—there lay a compass with a smoked glass face, an envelope, and a darker smear where oil had seeped out over years.

The envelope knew my name. Not “To Whom It May Concern” or the generic politeness of solicitors, but my name, written in my mother’s neat script, younger, looser, almost laughing. The postmark was a date that pre-dated me and yet somehow anticipated me; it felt like a trick. My stomach performed a small, needless somersault.

If you are reading this, the letter said, then you have found what I hid when I ran. The compass will not point north today; it will point to what you lost without knowing. Begin where the lions drink stone beneath the railway bridge. Time thins there. Be brave.

I read it twice, then a third time, hunting for the tell-tale hitch of a joke. There was none. The handwriting deteriorated towards the end, as if whoever wrote it—my mother? my almost-mythical aunt?—had been writing from inside a moving car, or a tremor. The compass, when coaxed upright, quivered, the needle skittish and sure, and ignored the magnet I fetched from the toolbox. It leaned, insistently, towards the south-east wall and held.

Below me, the house creaked with tiredness. Somewhere outside, a train shivered past, its long note a reminder, or a warning. I could have closed the lid. I could have slid the plank back into place and descended to the predictable geography of boxes labelled Kitchen and Donate and Keep. I could have laughed at myself—at the ridiculous notion that a tin and a note could rearrange the ordinary.

Instead, I began the litany of search: pockets, phone, keys. A scarf (not for warmth, but for courage), the letter folded and refolded to a sturdier shape, the compass cradled like an egg. My heart performed its usual drumroll—too loud, a shade melodramatic—for exams and earthquakes and this. I climbed down, each rung a rung deeper into whatever this was, and the dust followed me like confetti that had forgotten its celebration.

“Where are you going?” Mum asked, not looking up from the box she was conquering.

“To the bridge,” I said, as if that were an everyday destination, as if stone lions drank there as naturally as pigeons do. She nodded, distracted, and for a moment I saw her face as a map with missing roads; there were whole towns I had never asked about.

Outside, the air had that clean, metallic taste that comes before rain. The compass trembled in my palm, implacable, almost eager. It did not point north. It pointed, quite clearly, to the place where the search would have to start.

- Level 4 Lower (19-21 marks for AO5, 13-16 marks for AO6, 32-37 marks total)

Option A:

In the attic’s half-light, the trunk sits where the roof stoops, a dark rectangle among beams. Dust moves in slow constellations, tilting and settling; a sliver of afternoon climbs the rafters like a ladder of pale gold and stops short at the leather. Everything up here seems to hold its breath. The air tastes of dry timber and something faintly medicinal, a whisper of camphor that lingers at the back of the throat. It waits. Not new, not merely old—seasoned; stored; stilled.

Up close, the hide shows a history written into it: a palimpsest of scratches, rain-scars, the faint bloom where hands have polished it by accident. The stitching bites in like sutures; the brass studs are little coins of dull sun. Two locks sit side by side like shuttered eyes, lids greened with patient verdigris. The hasp is a stern mouth; the handles, rope-thick, have frayed into soft whiskers. A paper label (brittle as frost) still clings to one corner, its ink faded to a soft murmur of letters. When the light slides over it, the trunk does a strange thing—it seems to absorb the shine rather than throw it back.

It is heavy with what it refuses to say; not simply weight in the wrist, but the heft of silence: layered, compressed. The quiet here has a texture, a nap like velvet brushed the wrong way. Perhaps salt dried into the seams; perhaps a ghost of smoke and platforms—too easy a story, but it clings. The nameplate offers two initials; the second is rubbed nearly blank, as if someone has worried it back and forth, back and forth.

I rest my palm on the leather and feel a coolness that isn’t simply temperature; it is a kept cool, cellar-cool, a guarded climate. The lid yields a fraction, a breath—the hinge gives a cautious, almost polite sigh—and stops. The locks hold; they are not cruel, merely resolute. My hand tingles as if a pulse had travelled up from inside. What is kept is not loud. It is compact, folded, exacting. A secret like a small, clenched star.

The trunk is a custodian: a reliquary, a stubborn witness; also, a piece of furniture with scuffs and a split seam. Who sealed it, and what did they want to survive them? The answer remains closed, yet its outline is everywhere—the air, the dust, the scuffed floorboards. It has been carried and hidden; it has been noticed and left. It waits, as the room waits. It knows.

Option B:

By the time the ladder squealed under my weight, afternoon had thinned into that brittle gold the house kept for itself. Dust drifted like slow snow through the rafters; the loft smelled faintly of apples and old wood, a quiet, careful scent. Every box wore a label in my grandmother’s upright hand, neat loops marching across yellowing stickers: Winter Coats, Receipts, Letters (Private).

I told Mum I’d be quick—just sorting, nothing dramatic—and she’d nodded without looking up from the sink. Gran had been gone three weeks and the house seemed to breathe differently; rooms exhaled stories we’d never asked to hear. Up here, under tiles and sky, I felt like an intruder in someone else’s memory. Still, I knelt and opened lids: ribbons, postcards, a tin of buttons that tinkled like small rain.

At the back, half-hidden behind a moth-chewed suitcase, a narrow bureau sulked against the eaves. Its top drawer would not cooperate. I tugged; it stuck. I wriggled the handle, whispered something unhelpful, and tugged again. A dry scrape, a shrug—and it slid, grudgingly, into the light. Empty. Almost. The base was thicker than it should have been, as if the wood had a secret to keep. When I pressed the seam with my thumbnail, it shifted. A slip of card eased free, and beneath it lay a shallow cavity no bigger than a book. My heart misbehaved.

Inside was a small tin the colour of storms. The lid resisted, then gave with a sigh, as if it had been holding its breath for decades. Three things waited there: a brass compass with a hairline crack across its glass; a photograph, soft at the edges; and a folded paper, brittle, the folds whitened with age. The compass needle trembled, unsure. The photograph showed two people on a stony beach, wind at their coats—my grandmother unmistakable, her mouth lifted just so, and beside her a man I did not recognise. On the back, in that same tidy script, a date I couldn’t place and two words: Find me.

The paper was a map, not a road map but something older, pale-blue with threaded rivers and names like spells—Grayfen, Rook’s Edge, Blackwater. There were pencil marks: a small cross near a bend of water; faint numbers, coordinates sketched in a rush. I stared, the attic suddenly louder. Who had she hidden from us? Who was asking to be found, and why whisper it into a drawer?

I slid the tin into my backpack—carefully, as if it might bruise—and climbed down with my mind racing. Step one: decipher the coordinates; step two: compare the coast in the photograph to the maps in the library; step three: ask Aunt Elsie what she refuses to say. It felt foolish and necessary at the same time. The compass lay warm against my ribs. It might have pointed north once; now it seemed to point directly at the gap Gran had left behind.

- Level 3 Upper (16-18 marks for AO5, 9-12 marks for AO6, 25-30 marks total)

Option A:

It crouches at the far end of the attic, a stubborn animal made of leather and silence. Sunlight slants in ladders through the dusty window; the air is busy with glittering storms. Its lid, the colour of old chestnuts, is scored by scratches that stop at the brass corners.

Here, the locks sit side by side, pitted and patient. Their mouths are closed tight—clipped, almost prim—and the metal wears a faded green blush of verdigris. The straps lie flat, cracked into scales; the stitching frays into whiskers.

The secret it holds does not rattle. It does not shout. It is folded, carefully; it breathes slowly. If I lean close, there is a smell—peppery paper, dry leather, a ghost of orange peel—that feels like a memory I cannot place. Who tucked it there first? I am certain the secret is watching me, the way a kept word watches a mouth: waiting to be let out, and dreading it.

Perhaps it is nothing more than a letter, the ink bleached to tea; perhaps a photograph that refuses to smile. There might be a watch that no longer ticks; a brooch missing one stone, blue as a bruise. Each possibility lifts like a small bird and settles again; the trunk stays calm, as if my guesses hardly scratch its hide.

Meanwhile, the hinges make a low syllable when nudged—no; not today. The handle has sagged into its shadow, worn thin where a thumb would pull. Tiny nail heads line the rim in ranks; a few have loosened, leaving delicate moons of rust. If I look long enough, the scratches form constellations I can't quite read.

However, a secret is a kind of shelter as much as a story. The locks know this; they keep their counsel with stubborn grace. I rest my palm on the lid. The attic light moves on by degrees—paler now, almost white—and dust drifts down and down, again and again, like slow snow.

So it waits, and I wait. The trunk does not offer; I do not pry. In that quiet, the object grows larger than its edges, and the secret stays where it has always been: inside, folded; inside, safe.

Option B:

Morning slid through the narrow hallway and lay in thin squares across the carpet. The bulb above me hummed like a tired bee, the house breathing its long, old breath. I was meant to be finding spare batteries, not memories, but the cupboard was stubborn; it refused to give up anything without a bargain.

Instead, my fingers knocked a loose plank behind the hoover and something clicked. When I pulled the board again, it squealed and a thin envelope slid forward, dust soft as flour on its edges. Across the front, in careful ink that wasn't mine, a message: For the one who asks.

I hadn’t asked out loud, but I had been asking forever.

I slid my thumb under the flap and opened it carefully — not just old but careful — and found two things: a tiny brass key and a scrap of paper. The key was cool, as if it had been waiting. A sketch mapped the village in quick strokes: the post office, the church, the river like a black ribbon, and an X where the path bends under the hawthorn trees. Beneath it, four words, slanted and sure: Begin where we ended. June ’98.

I knew that script; it matched the loops on the recipe cards my grandmother tucked above the cooker. She died when I was small, leaving peppermint tins and questions. Dad, however, never answered those — not beyond a shrug and a tired smile. Why hide a key? Why map a path we all walked past? Why now?

The batteries could wait; something else had been switched on. I threaded the key onto a spare shoelace and dropped it around my neck, grabbed my coat, a torch that still worked, and the grit of being sixteen. Outside, the morning had sharpened. Clouds hung like folded letters; a dog barked at nothing.

I stepped onto the path that curved down to the river, the map buzzing in my pocket like a secret. Each footfall shook last night’s rain from the leaves. I knew the hawthorns, but this felt different, as if the ground itself were pointing. With each familiar fencepost, one thought kept returning: this was the start.

- Level 3 Lower (13-15 marks for AO5, 9-12 marks for AO6, 22-27 marks total)

Option A:

The trunk crouches in the far end of the attic, a low, stubborn shape with a patient shadow. Its leather is cracked like a dry riverbed; the corners are rubbed to a pale shine, and a thin line of sunlight lies across the lid. Dust sits on it in a soft coat, but the brass studs still glint, small and deliberate. When I step closer I catch a smell—musty paper and a breath of salt—as if it once sailed somewhere. It looks ordinary, almost plain. It waits.

Two locks guard the front like calm eyes; between them, the keyhole is a dark zero that watches. The straps sag a little, their edges frayed; the stitching runs straight as train tracks. Running my fingers over the surface, I feel patches smooth as a pebble, then ridges where the grain rises. The lid is heavy, it looks heavier than it is when you try it: the hinges give a long, protesting note. What secret does it keep, and why is it so patient—so sure of time?

Sometimes I imagine the secret is simple: letters tied with a faded ribbon; a photograph you half recognise; lavender in a tin. Other times it is stranger—rain caught in a jar, or a whisper that knows my name. Maybe it holds a map with a tear that matters, or a name that was changed. The trunk seems to understand this weight. It sits square and steady, holding its breath. I press my palm to the cool lock and feel only the chill, then I step back. Not yet.

Option B:

I found it by accident, wedged beneath a loose floorboard in Gran’s attic. Dust swam in a slant of light like slow snow, and the air smelt of old books and damp cardboard. The house made its patient noises—pipes ticking, rafters sighing. I had only meant to move the trunk; my sleeve snagged, the board lifted, and something thin and metal flashed.

It was a tin, the kind that held sweets, its paint flaked and lid stiff with rust. Inside lay a square of paper, folded into quarters so many times the edges were almost silk. When I opened it, a pressed violet fell out, and a map unfurled across my knees. Not a printed one. Hand-drawn in pencil, tracing places I knew: the church, the butcher’s, the path by the river. In the bottom corner there was a compass and, beside the old quarry, a circle. Next to the circle, one word: Begin.

A small tremor ran through me. It could be a joke, or a memory game Gran had planned and never finished. I remembered her saying last winter, in her thin voice, there are things you only see when you’re looking. The idea lit in me like a spark on dry grass. It was bold; it was foolish. It would not leave me alone.

I folded the map back—carefully—and slid it into my pocket. Boots, coat, torch, keys. I paused at the hatch, listening to the steady tick of the landing clock. Outside, the afternoon bruised into evening; the wind worried the fence. The first mark was near the quarry, beyond the allotments. I locked the door and stepped into the cold. Whatever Gran had hidden, or lost, or wanted me to find, I would start with that circle. I would look, and I would keep on looking.

- Level 2 Upper (10-12 marks for AO5, 5-8 marks for AO6, 15-20 marks total)

Option A:

Under the stairs, the trunk crouches. Its leather is cracked like riverbeds in summer. The brass locks bloom with green; the bands bite into the hide. When I brush it, the smell rises: warm, stale, a little sweet, like old books and raincoats. Scratches cross its lid like a map, routes to nowhere and everywhere. The lid is heavy; the hinges sigh, a tired whisper. It keeps a secret, tucked deep, like a flat stone at the bottom of a pond.

Inside, I imagine layers: paper, ribbon, a key, a photograph with faces that won't look at me. I don't open it all the way; I'm careful, almost polite. A cold breath climbs out and touches my fingers. What is it hiding? Not gold, I think, but something quieter, more dangerous—memory. Letters that stain the skin; a tiny bottle of sand; a music box that won't quite sing. I hear a sound, maybe its only the hinge; maybe it is the past moving.

Sometimes I sit with it; we share the stairs like tired travellers. I tell it nothing, it tells me nothing, but it waits and waits. The secret presses inside, patient, deliberate. I could fetch the key; I could break the seal; I could be brave. Yet I leave it alone: keeping is a kind of kindness, and opening is another. When I walk away, the hallway seems thinner, as if the house holds its breath. Under the stairs the trunk crouches again, old and stubborn, and the secret stays shut.

Option B:

I found it by accident, tucked behind a loose plank in the attic. The plank wobbled when I pulled the old trunk, and something small slid out and tapped my shoe. A tin box, scratched to silver. Dust got in my mouth, chalky. I knelt, and the floor whispered under my knees. Inside there was a folded paper, a coin, and a note. The paper was a map of our town, with faint pencil lines that curved and a star near the canal. The note said: Begin at the clock that doesn’t tick.

My heart didn’t race, exactly, but it pressed on my ribs. Grandad used to tell stories about hidden things; he loved riddles. He had lived in this house, in this very room. Was this his? A clue? Questions gathered and buzzed like flies in the light. The attic air felt too tight. I stood, wiped my hands, and tried to think. The clock that doesn’t tick. I pictured the dead clock above the market, stuck at twelve since forever. It had to be that, didn’t it?

Later that afternoon, with the map folded in my pocket, I walked down the hill. The street hummed with buses and voices, but the arrow on the paper pulled at me. Houses leaned towards each other, windows blinking; the town seemed to know more than it was saying. I didn’t tell Mum—she would laugh, or worry. I told myself this was nothing, just a walk. Still, every step felt important. At the market gates I looked up, and the search began.

- Level 2 Lower (7-9 marks for AO5, 5-8 marks for AO6, 12-17 marks total)

Option A:

The trunk sits in the corner like a sleeping animal, its leather scuffed and the locks dull with age. At first it looks ordinary. But the lid dips slightly, as if it remembers hands pressing it down. I run my fingers over the cracked surface; the texture is rough and it smells of old books and salt. Scratches cross the top like tiny roads. A frayed label clings by one string—no name, only a smeared initial. The hinges mutter when I nudge it, a stubborn sound. Silence.

However, the true thing hides inside: a secret. What is it? A photograph, a map? I imagine a folded note, written in a hurried hand. My heart beats faster, because secrets change the air, make it thicker, close to the skin, like fog that cant lift. Maybe it belongs to someone who never came back. Maybe it belongs to me, but I just dont know it yet. Finally, I rest my palm on the lid. It is heavy, heavier than it should be. I whisper a promise to open it—when I am brave enough. For now I keep the secret safe by not opening it; the trunk keeps me too, keeping my thoughts closed, waiting.

Option B:

Autumn. The attic smelled of old books and dust; thin light slanted through the hatch, searching the corners. The house was quiet except for the rain tapping, like fingers on a table. I climbed the creaking ladder and pushed aside boxes with old labels.

At the back behind a moth-eaten blanket, my hand hit a small tin box. It was tarnished and cold, with tiny leaves carved around two letters: M.R. The lid stuck. I pulled and it opened with a sigh; I opened the box, my hands shook.

Inside there were three things: a narrow brass key, a map folded into a star, and a photograph. The photo was faded but I could see a girl my age standing by a twisted bridge and a river shining. On the back someone had written 'Find the gate'. My heart beat like a small drum. Who left this here? Why me?

The map had a red cross and a scribbled arrow. I traced the route with my finger, the paper felt delicate. However I didn't know the place, not yet. Still, I knew what I had to do. I would follow the line, I would find that gate - the search started there and then.

- Level 1 Upper (4-6 marks for AO5, 1-4 marks for AO6, 5-10 marks total)

Option A:

The trunk sits in the corner like it has always been there. It is old and brown, the leather is cracked and dry and the lid has a scar across it. The metal locks are dull and stiff they look like shut eyes that dont want to wake up. When I touch it the skin is cold; it smells dusty, like old books. The handles bite my fingers they leave marks.

I think it holds a secret it holds it tight, like a breath in the chest. The straps hang loose, but still it feels closed, like a mouth pressed shut. Sometimes the lid whispers not really words just a small sound, I hear it at night and I dont sleep. The key is gone; or maybe it is hiding as well. The secret is: quiet and it waits. I wait too I listen I wait again.

It watches me, and it keeps it.

Option B:

Morning. The street was quiet and cold. Wet leaves stuck to the path and my breath looked like smoke. My hands hurt so I shoved them in my pockets and I kicked a stone. The sky was grey and nothing was moving.

My shoe hit something hard under the step and I jumped! In the mud there was a small tin box. It was brown and old. I pulled it out. It rattled.

I opened it. Inside was a crumpled note and a tiny map, like a kid drawed it. The arrow pointed to the park and then a big X. It said FIND ME. My heart went fast, I felt like a detective. Who put it there, why now, what if there was tresure, I didnt know. I started the search, I looked under the gate, then behind the wall, I kept walking, kept looking.

- Level 1 Lower (1-3 marks for AO5, 1-4 marks for AO6, 2-7 marks total)

Option A:

The old trunk sits in the corner. The lether is brown and cracked and it flakes. The lock has rust and there are to chains. I put my hand on it, its cold and rough and it kind of shivers. I think there is a secrit inside, like a small voice, like it breaths again and again. I seen it in a picture at nan's house once and then I think of the beach for no reason, waves going back and forward. I dont open it. The lid is heavy, it looks heavy, it watches me. you can almost hear it, but not really...

Option B:

I was walking behind the old shop and I seen a small key in the dust. It was a dull grey and it felt cold in my hand. You know when you just know something matters, I had that. It had a tag, it said 12, or maybe 21. I wasnt sure. I put it in my pocket and I looked around. My shoe was wet and I was hungry. There was no lock near, just bins and a cat that ran. I had to find where it fit. I had to look, like a game. I went down the alley to look more.