Insert

The source that follows is:

- Source A: 19th-century prose fiction

- Hard Times by Charles Dickens

An extract from a work first published in 1854.

This extract is from Charles Dickens's Hard Times, where townspeople and a surgeon work to rescue Stephen Blackpool from the disused Old Hell Shaft at dusk, using a windlass and torches, highlighting industrial danger, communal solidarity, and the tense uncertainty of his severe injuries.

Source A

1 When he said ‘Alive!’ a great shout arose and many eyes had tears in them. ‘But he’s hurt very bad,’ he added, as soon as he could make himself heard again. ‘Where’s doctor? He’s hurt so very bad, sir, that we donno

6 how to get him up.’ They all consulted together, and looked anxiously at the surgeon, as he asked

11 some questions, and shook his head on receiving the replies. The sun was setting now; and the red light in the evening sky touched every face there, and caused it to be distinctly seen in all its rapt suspense. The consultation

16 ended in the men returning to the windlass, and the pitman going down again, carrying the wine and some other small matters with him. Then the other man came up. In the meantime, under the

21 surgeon’s directions, some men brought a hurdle, on which others made a thick bed of spare clothes covered with loose straw, while he himself contrived some bandages and slings from shawls and

26 handkerchiefs. As these were made, they were hung upon an arm of the pitman who had last come up, with instructions how to use them: and as he stood, shown by the

31 light he carried, leaning his powerful loose hand upon one of the poles, and sometimes glancing down the pit, and sometimes glancing round upon the people, he was not the least conspicuous figure in the scene. It was dark

36 now, and torches were kindled. It appeared from the little this man said to those about him, which was quickly repeated all over the circle, that the lost man had fallen upon a mass of crumbled rubbish with which the pit was half

41 choked up, and that his fall had been further broken by some jagged earth at the side. He lay upon his back with one arm doubled under him, and according to his

46 own belief had hardly stirred since he fell, except that he had moved his free hand to a side pocket, in which he remembered to have some bread and meat (of which he had swallowed crumbs), and had likewise scooped up a little

51 water in it now and then. He had come straight away from his work, on being written to, and had walked the whole journey; and was on his way to Mr. Bounderby’s country house after dark, when he fell. He

56 was crossing that dangerous country at such a dangerous time, because he was innocent of what was laid to his charge, and couldn’t rest from coming the nearest way to

61 deliver himself up. The Old Hell Shaft, the pitman said, with a curse upon it, was worthy of its bad name to the last; for though Stephen could speak now, he believed it would soon be

66 found to have mangled the life out of him. When all was ready, this man, still taking his last hurried charges from his comrades and the surgeon after the windlass had begun to lower him, disappeared into

71 the pit. The rope went out as before, the signal was made as before, and the windlass stopped. No man removed his hand from it now. Every one waited with his grasp set, and his body bent down to

76 the work, ready to reverse and wind in. At length the signal was given, and all the ring leaned forward. For, now, the rope came in, tightened and strained to its utmost as it appeared, and the

81 men turned heavily, and the windlass complained. It was scarcely endurable to look at the rope, and think of its giving way. But, ring after ring was coiled upon the barrel of the windlass safely, and the connecting chains appeared,

86 and finally the bucket with the two men holding on at the sides—a sight to make the head swim, and oppress the heart—and tenderly supporting between them, slung and tied within,

91 the figure of a poor, crushed, human creature. A low murmur of pity went round the throng, and the women wept aloud, as this form, almost without form, was moved very slowly from its iron deliverance,

96 and laid upon the bed of straw. At first, none but the surgeon went close to it.

Questions

Instructions

- Answer all questions.

- Use black ink or black ball point pen.

- Fill in the boxes on this page.

- You must answer the questions in the spaces provided.

- Do not write outside the box around each page or on blank pages.

- Do all rough work in this book. Cross through any work you do not want to be marked.

- You must refer to the insert booklet provided.

- You must not use a dictionary.

Information

- The marks for questions are shown in brackets.

- Time allowed: 1 hour 45 minutes

- The maximum mark for this paper is 80.

- There are 40 marks for Section A and 40 marks for Section B.

- You are reminded of the need for good English and clear presentation in your answers.

- You will be assessed on the quality of your reading in Section A.

- You will be assessed on the quality of your writing in Section B.

Advice

- You are advised to spend about 15 minutes reading through the source and all five questions you have to answer.

- You should make sure you leave sufficient time to check your answers.

Section A: Reading

Answer all questions in this section. You are advised to spend about 45 minutes on this section.

Question 1

Read again the first part of the source, from lines 1 to 5.

Answer all parts of this question.

Choose one answer for each question.

1.1 How was the consultation conducted?

- together

- anxiously

- distinctly

[1 mark]

1.2 What was looked at anxiously?

- the surgeon

- the evening sky

- every face there

[1 mark]

1.3 What happened on receiving the replies?

- some questions were asked

- a head was shaken

- looked anxiously at the surgeon

[1 mark]

1.4 What colour was the light in the evening sky?

- red

- blue

- golden

[1 mark]

Question 2

Look in detail at this extract, from lines 71 to 80 of the source:

71 the pit. The rope went out as before, the signal was made as before, and the windlass stopped. No man removed his hand from it now. Every one waited with his grasp set, and his body bent down to

76 the work, ready to reverse and wind in. At length the signal was given, and all the ring leaned forward. For, now, the rope came in, tightened and strained to its utmost as it appeared, and the

How does the writer use language here to build suspense as the men haul the injured man up from the pit? You could include the writer's choice of:

- words and phrases

- language features and techniques

- sentence forms.

[8 marks]

Question 3

You now need to think about the structure of the source as a whole. This text is from the end of a novel.

How has the writer structured the text to create a sense of suspense?

You could write about:

- how suspense intensifies from beginning to end

- how the writer uses structure to create an effect

- the writer's use of any other structural features, such as changes in mood, tone or perspective.

[8 marks]

Question 4

For this question focus on the second part of the source, from line 71 to the end.

In this part of the source, the description of the rescued man as a ‘crushed, human creature’ is very moving. The writer suggests that even though the man is alive, his life has been completely destroyed by the accident.

To what extent do you agree and/or disagree with this statement?

In your response, you could:

- consider your impressions of the crushed human creature

- comment on the methods the writer uses to portray the man's destroyed life

- support your response with references to the text.

[20 marks]

Question 5

A national business journal is publishing a feature on working life and invites entries from young writers.

Choose one of the options below for your entry.

-

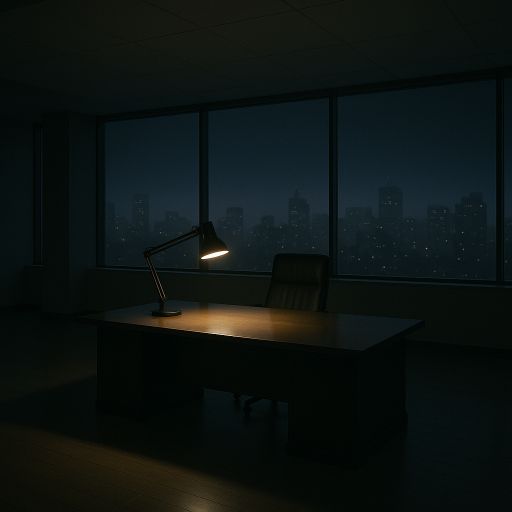

Option A: Describe a city office late at night from your imagination. You may choose to use the picture provided for ideas:

-

Option B: Write the opening of a story about dedication and sacrifice.

(24 marks for content and organisation, 16 marks for technical accuracy)

[40 marks]